Water | Sang Lee

I drove up to Gloucester early, hoping to beat traffic and shoot some photos of the neighborhood while there was still light to play with. I popped my head in to see if Sang was up for some quick portraits before service began. I found him prepping, chatting with his wife and mother-in-law, who all very warmly welcomed my intrusion. He introduced me to the team, kissed his wife goodbye as she stepped out, put on his robe for the photos, and then slipped back to the kitchen to continue setting up for dinner, quietly mentioning the rice on the way back in.

A Chopped winner, I’d first heard about Sang Lee from my brother, who cut his teeth in the New England seafood world before moving to Kenya and launching his own business. He knows the East Coast ecosystem—chefs, fishermen, importers, restaurateurs—and usually speaks about it with an amused distance. But after driving down from Portland to deliver product to Sang and chatting with him, he texted me that I needed to meet him. He told me he admired the way Sang honors tradition without being ruled by it, the way he brings both respect and pragmatism to his food, and how comfortable he is navigating that balance. His cooking, my brother said, was grounded in tradition but not constrained by it—open to local sourcing, to new fish, and to other possibilities many chefs at his level wouldn’t necessarily consider. It was also delicious he said.

By September 2021, the anxiety of the pandemic was beginning to ease and my parents-in-law, at home in Seoul for more than two years, were finally planning a visit back to Boston. Our reunion felt unreal after the wait. My brother was back in town, too. I had reached out to Sang to arrange the proverbial pandemic parlance, “homakase,” an at-home sushi service he was offering that laid part of the foundation for the restaurant to come.

Sang arrived with his stepdaughter, who served while he took over our small open kitchen. We’d invited friends—a local family, like us, recently reunited with parents visiting from Korea. Our daughters sat on stools at our kitchen island eating maki Sang had rolled for them, watching him prep dinner before they drifted upstairs to play.

Sang’s stepdaughter poured the wines my father-in-law had gifted me before the pandemic—bottles we’d vowed in the throws of lockdown to save for this night. From the first course, the food spoke: beautiful, minimalist presentation with preparations that put the fish confidently at the center. No need for accoutrement. Mastery immediately evident and increasingly pronounced as the courses rolled on. It was an unreal meal.

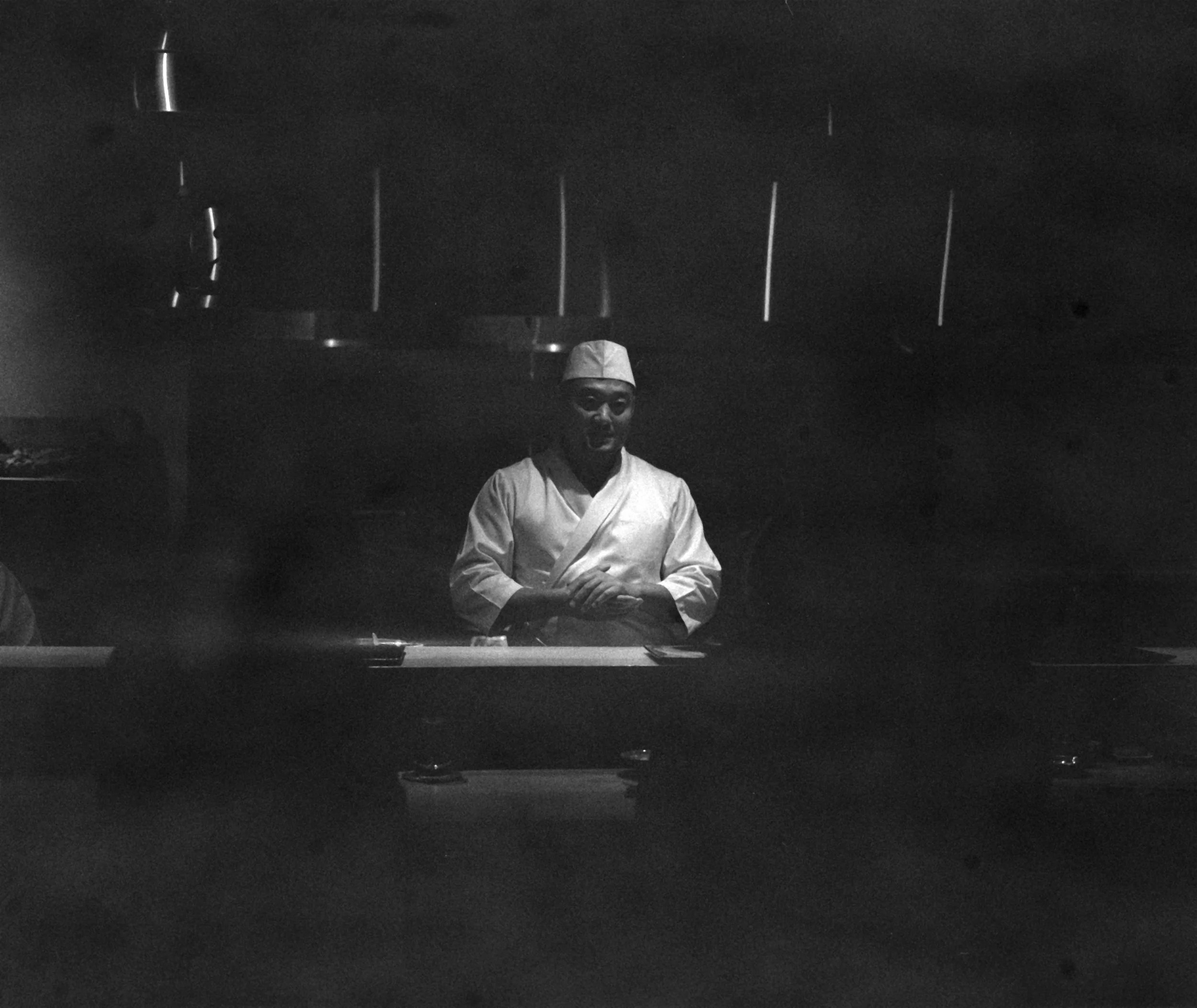

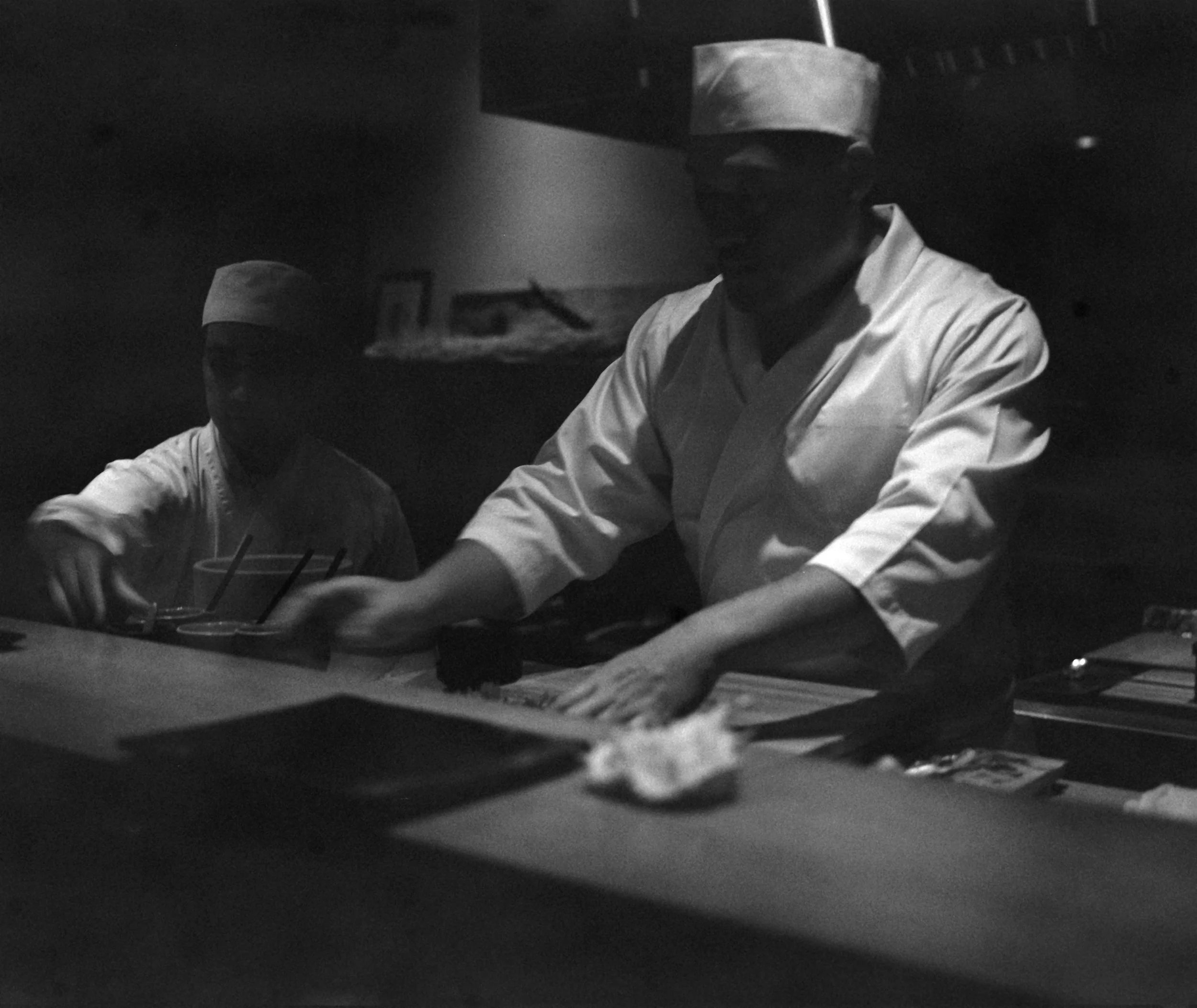

In person, Sang carries himself like a North Shore local—focused, calm, unhurried, with the steadiness of someone who’s at home where he is. His cooking reflects the path that brought him here: Japanese standards, New York training, Korean sensibility, and New England practicality. As I sat at his eight-seat counter through service of his 18-course omakase menu, chatting with him intermittently as he introduced each new plate, this character was foundational. His food is ambitious without pretense or ego, strikingly delicious and unusually thoughtful in its composition without being unnecessarily inventive or overwrought.

Sang’s menu, like his life, is a study in movement and return. From Seoul to Boston, New York to the North Shore, his food is predominantly local in source, global in influence, and unabashedly human in delivery.

What follows is presented as Chef Sang Lee presented it to me: a story told course by course, each plate an artifact of memory, migration, care, and his own authenticity.

Otsumami

Hotate | Local live scallop with lemon juice, lemon zest, roasted Japanese sea salt, and fresh wasabi from Shizuoka, Japan

My father was a police officer who became a detective—a hyeongsa. Korean detectives are different from their American counterparts; they’re more on the street, waiting overnight in their cars for bad guys to show up, then running out to grab and arrest them. He worked at Jongro Police Department in Seoul—a kind of infamous place. My father was the toughest person I’ve ever met in my life—he had zero fear, absolutely none. He was incredibly strong—a fourth-degree black belt in Yudo. He was charismatic, tough on the outside, but soft inside. He was also a huge foodie. He didn’t cook much, but he knew all the really good restaurants, the hole-in-the-wall spots and the fancy places alike and he would take me as a boy. I got that from him: my love for eating. There’s nothing I don’t like.

Chawanmushi | Japanese egg custard with golden-eye snapper

My mother is outwardly softer. She loves to cook and to feed people. She came from Jeonju, a city famous for its food, via Muju. Her grandmother was a famous cook in her village, people said she was better than the palace chefs. My mother’s side of the family was all about hospitality and food. Every mom is a good cook, but my mom was exceptionally good. I grew up surrounded by good, loving food and developed an awareness and appreciation for it.

I remember to this day my father’s friend from Yeosu sending a big Styrofoam box packed with seafood on ice—live crabs, shellfish, fish—it was like a treasure chest. We ate sashimi that night and it changed my life. I was eight years old, and from then on, my favorite places were always sushi bars. That delicate raw fish flavor—that was my favorite thing in the world.

Gloucester lobster steamed with sake and served with a Maine uni sauce

My father passed away when I was nineteen. Before that, my first girlfriend moved to America. Her mother adored me and invited me to come, learn English, and stay long-term. That’s how I came to Boston. On September 11, 2001, I flew from Incheon and was supposed to land at JFK, then continue on to Logan. When I was about an hour away from New York City, the towers came down. It was my first trip out of the country—by myself, barely able to speak English. The only thing I understood from the in-flight announcement was ‘emergency landing.’ We landed in Minneapolis. Two days later we flew again—ours was the first plane allowed to take off after 9/11. As we landed at JFK I could still see smoke rising from the city. There was no connection to Boston; I felt lost. A father taking his daughter to start school at Harvard offered me a ride and I eventually got there.

Shime saba isobemaki | Cured Gloucester mackerel with chives, pickled ginger, shiso, and sesame seeds

My first job in the U.S. was a cashier at a dry cleaner, but I had already worked in restaurants back in Korea, so I started looking for kitchen work as soon as I got settled. I found a job at E Shan Tang in Allston—an acupuncture clinic. The owner, Dr. Wong, was Chinese, had lived in Korea, and gone to college in Japan. He spoke Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and English, and he’d learned sushi while in college. His plan was to open a small Japanese restaurant and he said he’d help me with my Green Card, so my first sushi training began there—on a massage bed and in the tiny kitchen behind the clinic. That’s when I discovered my passion for it as a chef. The restaurant never happened and I didn’t get my Green Card there—but I knew I’d found what I wanted to do. After that, I got a job at Oishii 2 in Sudbury—a well-known sushi restaurant considered one of the best in Boston. Chef Kung hired me, and I learned fast. I was like a sponge. I spent two years there.

Gloucester red sea perch grilled with binchōtan and cured with ume; served with grated daikon, soy sauce, and lemon juice

I left Massachusetts for New York and started working in sushi bars on Long Island before landing a position at 1 OR 8 in Williamsburg. That’s where I did omakase service for the first time. I fell in love with it—the quality, the timing, the intimacy with the customers. After that, I went to Sen Sakana in Midtown Manhattan, a large restaurant built around Nikkei cuisine—Peruvian and Japanese fusion. I experimented with Peruvian ingredients but kept it subtle and balanced. We got a New York Times star, and the sushi section was the best part of the review. Still, I realized that wasn’t the kind of sushi I wanted to make for the rest of my life. I wanted to return to pure omakase. My last stop before opening my own place was Shuko, owned by Chef Nick Kim. He had been head chef at Masa—the only three-Michelin-star Japanese restaurant in the U.S. Masa was like a temple of sushi, and Shuko carried that lineage into something more personal. Working there was another level. I learned so much from Chef Nick. I stayed a little over a year. That was my last restaurant working for someone else.

Ankimo | Gloucester monkfish liver with narazuke and ponzu

I first came to Gloucester in 2012. There was a restaurant called Madfish Grill, right on the water—beautiful spot, wide open windows, live music, people laughing. It was a magical place for me. My friend Jordan Rubin, aka “Mr. Tuna” set up a sushi bar and asked me to help out for the summer. My plan was just to work for a few months, make a little money, travel, and then go back to Korea. My driver’s license was about to expire, and I thought I had to leave. But that summer, I met my wife. I told her I was going to go back, and she told me she wanted me to stay and help me figure things out. I was shocked, but it felt meant to be. I proposed to her on Salt Island off Good harbor beach. We got married the next year in a back yard next to the Paint Factory, and just like that, I became part of her family. Suddenly, I had four kids in my life. It was a beautiful change. They welcomed me completely. I love them, and they love me. After a few years, I went back to New York briefly to work at 1 or 8 and continue learning, but when I came back, I realized Gloucester wasn’t just where she was from—it had become home for me, too. But I got a head sushi chef job offer at Sen Sakana six months later, so we decide to move back to NYC.

Nigiri

Akami zuke | Lean marinated bluefin tuna from Gloucester

We came back to Gloucester for good in June of 2020, right in the middle of the pandemic. Everything was shut down, and nobody was eating out. I started making sushi at home—curbside pickup, small pop-ups, whatever I could do. People would drive up, and I’d hand them boxes at the door. In January 2021, a restaurant in town called Tonno closed for a month because of COVID, and I asked the owner if I could rent the kitchen to do omakase takeout. I made high-end New York–style boxes—wooden trays, beautiful presentation. As soon as I started, it became wicked popular. That’s really how Sushi Sang Lee began.

Madai | Sea bream, Japan

I use about seventy percent local fish and thirty percent from Japan. Fishermen I know in Gloucester will stop by with unusual, lesser-known species most people don’t eat. Around here they call them ‘trash fish,’ off-catch from fishing for striped bass or other marketable species they’d usually throw back. But some are incredible and unusual to eat—firm, sweet, really special. Those are the ones I add to the menu and build connections around. One of them, the northern stone crab, became one of my signatures. Sweet, deep-sea crab. You can’t keep them in tanks or ship them—they die right away. They live four hundred feet down, caught only in lobster traps thirty or forty miles offshore. They’re an incredibly special ingredient unique to my menu.

Botan ebi | Spot prawn

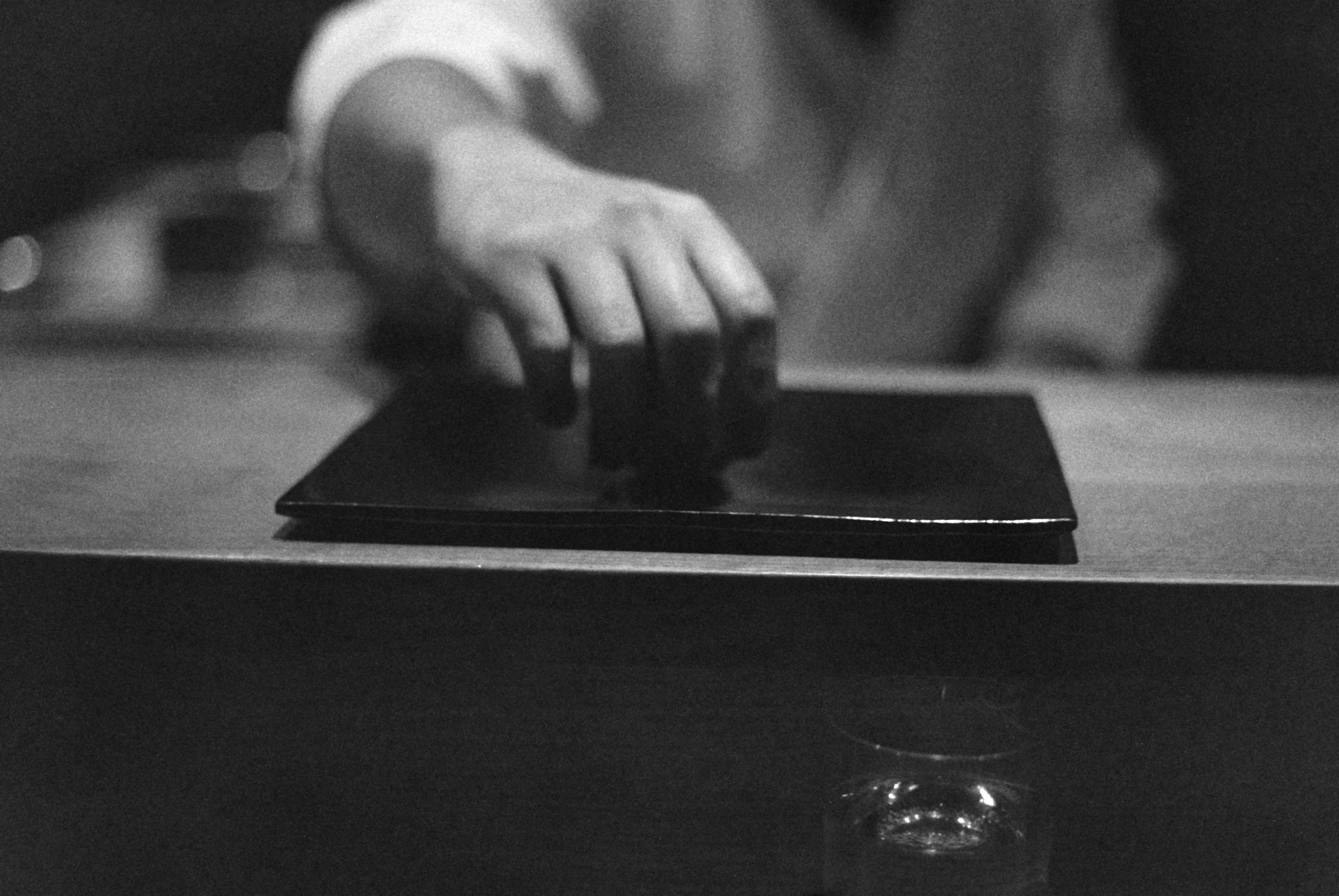

The rice I use is Yukitsubaki—the best in Japan, maybe in the world. They actually won the international rice award five years in a row. It’s grown in melted snow water, so it has lots of minerals. The flavor, the texture—everything about it is incredible. The brownish color comes from the vinegar I use, called Yohei. It’s made from sake lees—the leftover rice from sake brewing. It’s very strong and very dark—almost like soy sauce—with a distinct smell and flavor. During wartime in Japan, vinegar makers were ordered to stop using rice to preserve rations. Yokoi figured out how to make vinegar without rice. Back in the day, it was the cheapest vinegar you could buy. Now it’s the most expensive. It was born from the toughest of times just like Sushi Sang Lee.

Ikura | Alaskan chum salmon roe

With any cuisine, I believe less is more. Simplicity, minimalism—that’s my mojo. Especially with sushi. Fish is the most delicate protein; if you put too much on top, you lose what’s best about it. You cover the flavor instead of revealing it. When I meet a new fish, I start with nothing. No seasoning, no sauce, no vinegar—just the fish itself. I taste it raw and try to understand it. The first thing I look for is the ‘down flavor’—the flaws, the bitterness, the smell, the fishiness. Once I find that, I think about how to take it away. Sometimes it’s a salt cure, sometimes a quick smoke, sometimes a bit of vinegar. Once that down flavor is gone, what’s left is pure, and then you can bring out what’s naturally beautiful in it. That’s the whole philosophy—don’t fight the ingredient. Respect it, study it, and let it tell you what it needs. I try to take the same approach with myself: recognize the flaws, remove what clouds the essence, and work toward being a better human being.

Sawara | Local Spanish mackerel smoked with wara (rice straw)

My kitchen is my home. I spend more time there than anywhere else. Thirteen, fourteen hours a day, four days a week, and even on the other days I’m still there, eight hours or so. It’s where I live. When you come in for omakase, I’m inviting you into my home. It’s not a restaurant—it’s my kitchen. I’m preparing fish for dinner, the same way I would at home, just with you sitting in front of me. It’s very personal, very intimate. Only eight seats. Every guest sees everything I do. There’s nowhere for anyone to hide, and that’s what I love about it. I always encourage guests to eat the nigiri immediately, before the flavor and the energy disappear.

Kinmedai | Golden-eye snapper, Japan

You don’t need much—just good rice, good vinegar, good soy sauce, good wasabi, a good knife, and good hands. People think sushi is about tricks or presentation, but it’s not. Every ingredient has to be perfect on its own, and then your hands have to know what to do. The rice temperature varies depending on the fish; the amount of wasabi changes, too. It can’t be too hot or too cold. The knife has to move the right way. It’s repetition. You respect the ingredients, you respect your tools, and you train your hands until they move without thinking. That’s sushi.

Uni | Hokkaido Sea urchin, Japan

I believe cooking and music share many similarities. If you sing someone else’s song, you’re a cover band. To become an artist with food, you need your own style. For a long time I cooked other people’s songs—Japanese chefs, New York chefs. You learn their flavor, their rhythm, their timing. But eventually, you have to find your own. That’s what I realized when I came back here. Gloucester gave me that freedom and inspiration. This town gave me everything I needed. It gave me my new family and my own business. I dreamed for over twenty years of having my own place—and it happened here. I thought I could open in New York pretty easily, but after all the tough years I realized, I don’t need to. I can’t make Gloucester-Cool in New York City. Now, I’m singing my own song.

Suimono | Local littleneck clam sake soup

I’m a water-being person. In Asia, they say everyone has an element—earth, wood, water, fire—and mine is water. I’ve always felt it. I feel comfortable with water; it gives me energy and peace. Gloucester is surrounded by it on all sides. It’s the oldest fishing port in America, a real working harbor with history everywhere. When I came here, I felt something deep, like I’d been here before. It felt like coming home. I believe in reincarnation, and I really think I lived here in a past life—maybe as a fisherman or someone who worked on these docks. There’s a calm I get here that I can’t find anywhere else. It’s why I stay close to the ocean. It reminds me who I am.

O-toro | Bluefin tuna belly, Gloucester

On her last visit, my mother brought sesame seeds from Korea. I’d been using high-quality Japanese sesame, but hers were twice as good—richer, more aromatic, just better in every way. Now I get them from Korea. She even made kimchi in my prep kitchen. Not in the main kitchen, of course—she used the secondary one in the back, just like at home. The smell filled the place. It made me so happy. It’s funny—after all the years of training in other people’s kitchens, in Boston and New York, sometimes the best ingredient still comes from my mother. It reminds me where I come from, and why I do this.

Anago | Conger eel, Japan

I don’t judge people—I don’t judge anything. Politics, religion—it doesn’t matter. Everyone has their own way of thinking, their own reasons for what they believe. I just try to understand, to respect it. The world’s already divided enough. I’ve learned that when you listen instead of judge, you find connection. It makes life simpler, lighter. I focus on what I can do—making good food, being kind, staying humble. That’s all that really matters.

Dessert

Dashimaki tamago | Japanese egg omelet

Now people come visit me from everywhere, and I’m making what I call Gloucester Edomae. In Japanese, “Edo” means “Old Tokyo” “Mae” means “in front of” — it’s the traditional sushi style that started near Tokyo Bay, where chefs worked with whatever fish came in that day. They cured it, marinated it, made it last, but kept everything simple and honest. That spirit is what I follow here in my restaurant. I use the same methods, but with a focus on Gloucester fish — local, seasonal, distinct. It’s this meeting. Old Tokyo technique, New England soul. That’s Gloucester Edomae.

Yuzu mango sorbet with fresh green shiso and dried red shiso flakes

I truly believe my father is here with me—in Gloucester, in the restaurant. He’s looking out for me. I never thought he was gone; I still talk to him. Realizing my father was never really gone—that he’s still with me—helped. It changed how I see life. I know he’s watching what I do. Sometimes I imagine him sitting right in front of me at the sushi bar, watching me work. I couldn’t have gotten here without him—his strength, his spirit. That’s why I try to do my best every day. Everything I make, everything I build, is for him. I just want to make him proud.

Sang Lee is the chef-owner of Sushi Sang Lee, an eight-seat omakase experience in Gloucester, MA, and the first chef to bring Edomae-style sushi to Massachusetts. His food reflects his classical training in New York and Boston and the resources of the New England coast. At home in Gloucester, he is devoted to his wife and four step-children.

Written by Chessin Gertler with Sang Lee | Photography by Chessin Gertler