Purpose | Stefan Ytterborn

In November 2021, in the suburbs west of Boston, I rode a CAKE motorcycle for the first time. I took out the Kalk—the lightweight, off-road-oriented flagship—and the Ösa, a smaller, modular, utility-driven model. It was on this sunny, unseasonably warm weekday morning that I threaded through quiet Metrowest roads in jeans and a T-shirt, flying past dog walkers, runners, and lawn crews whose heads turned in unison at the sight of the bikes. I stayed out past the test-ride window, got a call from the rep, and missed my next meeting.

CAKE was the poster child of the two-wheeled new-mobility movement: minimalist, utilitarian, visually distinct electric motorbikes. In both motorcycle and broader mobility circles, CAKE felt ascendant. Media coverage framed the company as reshaping the future of mobility—compressing sustainability, new aesthetics, and utility into a fresh manifestation of what a motorized two-wheeler and the company behind it could and should be, while still remaining familiar enough to not diverge entirely from the traditional form factor. With hundreds of international awards and constant features across the design press and beyond, CAKE’s rise seemed inseparable from the broader transportation narrative of the moment.

The February 2024 announcement of bankruptcy landed like a punch to the stomach. It carried for me the strange emotional mix of a favorite restaurant closing and that of a political candidate I assumed had it in the bag suddenly losing. Immediately—like many—I wanted to understand what had happened.

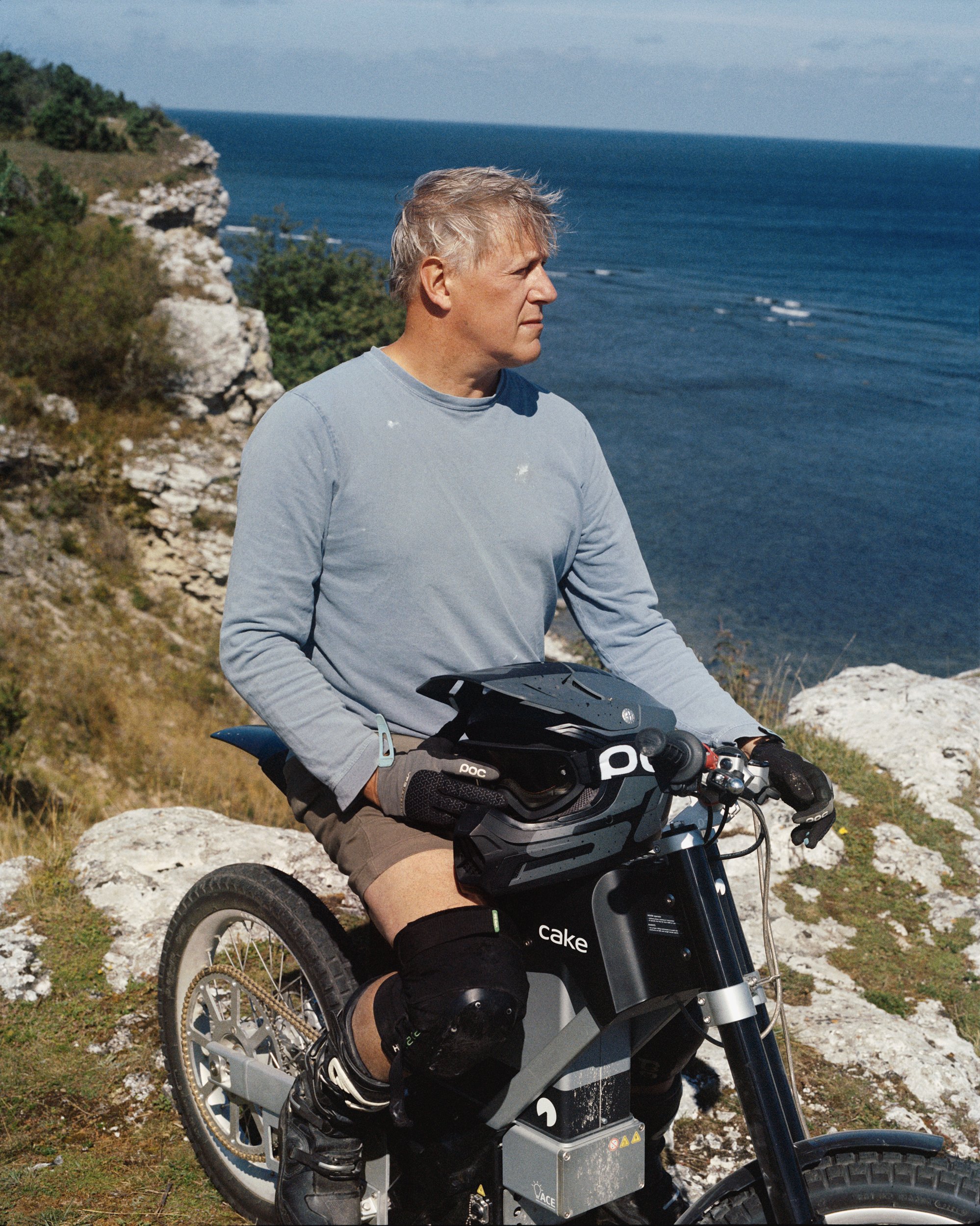

Prior to launching CAKE, Stefan Ytterborn founded POC after leading some of the most influential shifts in IKEA’s contemporary identity; a prodigious founder, designer, strategist, and creative. I asked Ytterborn for an unsweetened account of CAKE’s saga. We discussed the foundations of his career, the thinking that culminated in the company’s founding, its successes, the mistakes, and where he’s headed next. What Ytterborn shared is the story of a life’s work still evolving, shaped by a relentless desire to innovate and redefine through greater purpose.

Despite an ending that wasn’t fairytale, I can’t remember being this inspired by a conversation—as a designer, as an artist, as a founder, and as someone who loves, more than almost anything, the thrill of two-wheeled motion.

Chessin Gertler

Purpose

I’ve basically been an entrepreneur my entire adult life—42 years now as a founder and CEO with partners. Looking back, there’s always been one common denominator: purpose.

I started on the furniture side when I was 18 or 19, importing contemporary design from Italy, Spain, France. But what really hooked me wasn’t the aesthetics in isolation, it was the history behind them. I went deep—from the late 1600s through to the mid-80s—studying how objects changed as society changed.

You realize that preferences in the market are never static. They’re shaped by conflict, politics, social shifts, innovation, manufacturing technologies. When you look at a chair or a lamp from a certain period, you’re really looking at a snapshot of the values, aspirations, and constraints of that society.

That way of thinking—objects as the materialization of broader forces—has been a compass for everything I’ve done since.

From there I started my own business around contemporary Swedish design, ended up in Milan with some success, and eventually IKEA brought me in to lead a project called IKEA PS, launched in 1995. That was a turning point. It helped shift IKEA from being perceived as a copycat to actually offering original, independent design within its constraints: flat packs, price points, global logistics. It showed me how design, done correctly, can re-position an entire company without abandoning its fundamentals.

After years in furniture and household goods—glassware, ceramics, pots and pans, a lot of work in Finland and globally—I started to feel that something was missing. I was successful, but I was missing a certain density of purpose.

I’d been a ski racer when I was younger, and when my older kids, Karl and Nils, started racing, I returned to that world—this time as a worried parent. I was watching children training at high speed with what I felt was inadequate protection. At the same time, you could see broader societal trends: increased focus on health, safety, gated communities, insurance. Everything was pointing towards people protecting themselves more.

That led directly to POC, which started with a very clear mission: “To save lives and reduce the consequences of accidents”

First for skiers, and then for cyclists. That mission carries an obligation. If you say that out loud, you have to do everything you can to actually improve performance and safety. It’s not just a slogan.

CAKE came later, almost by accident. I’ve always been a motorcycle hater in the traditional sense. If a Harley roars by, my instinct is to put a finger up and wish it away. I never romanticized that culture.

But around 2012 or 2013 I encountered an early electric motorcycle at a trade show. The idea that you could ride in the forest without disturbing and without polluting was incredibly exciting. I started buying these early bikes, riding them, and quickly realized the market hadn’t adapted to the characteristics of an electric drivetrain. The hardware—chassis, suspension, everything—was still thinking in combustion.

That’s when the idea crystallized: build a company explicitly around optimizing everything for an electric drivetrain, and use that to push both off-road riding and urban transportation into a different future.

Design

I have a very pragmatic view of design. For me, design isn’t something that either exists or doesn’t exist; it always exists. The only question is how well the design process has been executed.

Design is how strategies become real. It’s how ambitions, values, and constraints take material form. If a company’s strategy changes, its design will follow—whether they admit that or not.

With CAKE, we didn’t sit down and say, “Let’s make something that looks futuristic or Scandinavian, or whatever.” We started from parameters:

We want to combine excitement with responsibility.

We want to minimize environmental footprint.

We want to express durability and technical honesty.

We want to show that electric is its own category, not just an electrified version of old motorcycles.

Those constraints and ambitions led the design.

We minimized plastics, for example, and made the frame the hero—visually and structurally. We tried to reduce the number of covers, masks, and hidden structures. If you look at most motorcycles, everything is wrapped in plastic. We did the opposite: expose the structure and make that the aesthetic.

My own background also matters. I’m much more of a cyclist than a motorcyclist, so the typology naturally ended up closer to bicycles than to traditional motorcycles. That upset a lot of people in the motorcycling community—“it’s ugly,” “it’s stupid,” and so on. But that was part of creating a new category.

Haters

If everyone likes something immediately, it’s probably too generic.

Whenever you introduce something with real newness—whether in function or form—you will get resistance, especially from laggards and from people deeply invested in the existing category. That resistance is a signal.

My rule of thumb is: Unless you have at least 50 percent haters when you launch, you’re probably not pushing far enough.

At POC and at CAKE, the goal was always the same in simple terms: Better performance and better looks.

Serve the market with something that performs better, and that people can love—even if half the world initially hates it. That’s where I see the intersection of art and sports: performance and functionality combined with a strong, sometimes polarizing visual identity.

Sustainability

The mission at CAKE was: To inspire towards a zero-emission society by combining excitement with responsibility.

Responsibility, in our case, included the entire lifecycle.

We tried to minimize plastics. We looked at manufacturing footprints. We built assembly in Taiwan and Sweden so that instead of shipping 26 finished bikes in a container, we could ship parts for 250 bikes and assemble closer to the customer. Long-term, the idea was to localize manufacturing of key components—CNC parts and similar—rather than shipping everything from a single place.

We also partnered with Vattenfall, a major Swedish energy provider, on what we called the fossil-free bike. That project forced us to analyze everything down to the smallest screw: What is the real emissions profile of each component? Where are the true hotspots? It pushed the whole sustainability conversation to a different level of detail.

At the same time, I think patience is an under-discussed part of sustainability. You can’t change user behavior or industrial systems overnight. You need time—for mindsets, for technology, for infrastructure. We were lucky in one way: capital was available at that time to go deep on these questions. Today, with the market focus shifted to defense and AI, I’m not sure we’d get the chance to do it at that depth.

Global

Our ambitions were always global. But we made a deliberate choice about where to begin.

Our primary target was urban and professional transportation—people commuting, delivering, working in cities on two wheels. The idea was that cars and internal combustion vehicles would be pushed out of city centers over time, especially in Europe, and smaller electric two-wheelers would become a core part of that infrastructure.

But we started with off-road for a reason: harsh use is the best way to prove durability. If you’ve got bikes jumping 20 meters and taking abuse in the woods, that’s an extreme testbed. Off-road allowed us to:

Stress test durability and component choices

Build credibility in a demanding environment

Learn fast and feed that knowledge back into urban-focused products

The long-term plan was never to be an off-road brand. In our models, no more than about 10 percent of revenue was ever supposed to come from that side. The other 90 percent was always meant to be urban and professional transport.

Bankruptcy

There were several layers to it, but the short version is this:

A failed late-stage funding round

A bridge solution that made us uninvestable

A hyper-growth cost structure we couldn’t sustain

In late 2022, we were preparing a Series C round—about $50 million—that would carry us to cash-flow positive by late 2026. We started to feel resistance in the fall. We didn’t close the round.

To keep the company alive while we kept fundraising, we took on convertible loans from one of our major investors, Swedish pension fund AMF. They supported us multiple times. I also put in more of my own money. At the time, it felt like the only way to survive until we found a lead investor.

Then March 10, 2023 came—Silicon Valley Bank collapsed. The late-stage funding market basically froze. According to TechCrunch, where there had been around 275 late-stage deals the year before, there were three or four in 2023. We were trying to raise into a market that had almost disappeared.

We shifted from chasing VCs to chasing strategic investors. Deutsche Bank/Numis helped us talk to big automotive players—Volvo, Ford, GM, others. But at the same time those companies were dealing with their own crisis: falling EV demand, massive capital needs in their core business. Everyone acknowledged that two-wheelers would be important for urban transport, but no one wanted to expand their portfolio into a small, loss-making startup just then.

Meanwhile, every convertible loan we took to buy more time was quietly sealing our fate. From the outside, it looked like support. But structurally, it meant that:

Any new investor’s money would first go to paying back those convertibles

Very little of that new capital would actually reach operations and growth

The upside for fresh investors became too small to justify the risk

We had accidentally dug our own grave. By solving a short-term liquidity problem, we made the company structurally unattractive to any new capital. Three days before we filed, I was on the phone trying to get a last bridge in place while our CFO was literally standing in court with the bankruptcy filing in his hand, holding it until the legal cut-off time for payroll and obligations. At four p.m., we had to drop it.

That was it.

Growth

CAKE’s growth plan was the result of both investor pressure and my own ambition. And I take responsibility—I said yes.

Our original plan was to sell around 70,000 units by 2030. That was already ambitious. But the whole ecosystem—consulting reports, market analysts, investors—was projecting huge growth in the electric two-wheeler space. People were saying, “Total Addressable Market is this big, you should be going for 300,000 units instead.”

Hyper-growth is contagious. Once you start planning for that scale, you have to pre-invest in everything:

Headcount

Manufacturing capacity

Development pipelines

Market presence

Those costs hit your P&L long before the matching revenues arrive. If the projected growth doesn’t materialize, you’re stuck with a fixed cost base that’s completely misaligned with reality. You become slow to react and slow to cut.

Looking back, I regret not sticking to my guns about more organic growth. I should have been stronger in saying, “No, this is the pace that makes sense for the product and the market.” Maybe we wouldn’t have gotten the same funding, maybe we wouldn’t have had the same PR highs—but we might still be here.

At the time, the investor mantra was: “direct-to-consumer.” This was also a big factor. For software, for mattresses, for shoes—and apparently for $5,000–$15,000 electric motorcycles, too.

In reality, this was a flawed match. When you’re an unknown brand asking someone to spend that much on a vehicle, they are not going to buy it from their sofa. They need to test ride it.

We learned that quickly. Whenever we were able to offer test rides—at CAKE hubs or pop-ups—we had a 17% conversion rate. That’s huge. It proved demand was there.

The problem was reach. With a pure DTC model, we simply couldn’t offer enough test-ride access. So in 2022 we started expanding:

Setting up CAKE hubs we owned

Working with distributors in markets like Japan, Korea, and Thailand

Talking to partners in Mexico and China about localized manufacturing on license

Opening up to external retailers, not just our own stores

But that pivot was late. We were still carrying a DTC-shaped cost structure while trying to build a more traditional distribution network in parallel. With time and a different balance sheet, I think that evolution would have worked.

Today

Even in the best case, running a company is never smooth. It’s always about dealing with problems—just in different colors.

If we’d found a bridge that truly solved our ability to survive, I still think we would have had to radically downsize to match a more modest reality. The analyst projections for the category were simply too optimistic. The macro environment—interest rates, inflation, EV fatigue—hit harder and lasted longer than people expected.

So in my imagined “perfect” scenario, the next 18 months would have been about:

Shrinking the cost base

Focusing on fewer core products and key markets

Rebuilding towards a slower, healthier growth curve

And then, from that leaner base, we could have accelerated again when conditions improved. That’s the version I think about sometimes—not as a fantasy, but as a design exercise in what should have happened operationally.

Lessons

A few things:

On funding: Be extremely careful with bridge structures like convertible loans, especially when they’re large and concentrated with a single investor. They can quietly make you uninvestable. Solving one problem can create a much bigger one later.

On growth: Don’t outsource your sense of reality to market reports and investor pressure. Organic growth is not a lack of ambition—it’s often the only way to build something that can actually last.

On distribution: Match your sales model to your product. If people need to touch and test it, build a system that allows that early, even if it’s less “scalable” on a spreadsheet.

On design: I’m doubling down on the idea that design is strategy, not cosmetics. And I still believe in the 50% haters rule.

Futures

After 42 years of being a CEO and filing 520 monthly reports, I’ve decided: I will never be a CEO again. Right now, I’m involved in several things—all of which are roles that are more advisory and collaborative.

I started a design and communication agency with some of my former CAKE colleagues. It’s called Com Tru. We’re working on performance-oriented products again—in equestrian, fashion, outdoor—very aligned with the POC journey in terms of materials, making, and performance, but across different categories.

My two sons, Karl and Nils—who were also co-founders at CAKE—are building a new electric two-wheeler brand. It’s very much informed by what we learned at CAKE, but it’s their project. The plan is to hit the market around early 2027, and I’m involved as an advisor and father, not as the person in the CEO chair.

Beyond that, I sit on a number of boards, advise a range of companies, and try—still not very successfully—to say “no” more often so I don’t spread myself too thin. My hope is to stay healthy and keep working for another 20 years in a way that leverages everything I’ve learned.

Legacy

I hope people see that, even though CAKE didn’t make it as a company, a lot of good came from it.

We delivered almost 7,000 bikes around the world between roughly 2020 and 2023. We pushed the category forward in design, sustainability, and perception. We got some people to leave their cars at home—sometimes for a CAKE, sometimes for a Vespa, sometimes for something else. And there’s a whole community of owners out there still riding, supported by partners servicing the bikes and supplying parts.

To me, that matters. Failure at the corporate level doesn’t erase the value of what was built, or the lessons that live on in the next thing.

Written by Chessin Gertler with Stefan Ytterborn | Photography courtesy of Stefan Ytterborn