Evolution | Parlee

In Beverly, Massachusetts—an hour north of Boston, in a nondescript warehouse pressed up against the commuter rail tracks—Parlee is making some of the best carbon-fiber bicycles in the world. The company is in the midst of evolution, with its next generation of bikes driven by renewed operational momentum and a clearer sense of direction.

Over the last two years, under the stewardship of John Harrison—a longtime technology executive and operator who came to Parlee as both a builder of durable businesses and a Parlee rider, himself—the cult framebuilder has undergone a period of major investment, by its own account surpassing the prior decade. New capital in has fueled accelerated product development, refined internal processes, expanded dealer recruitment, and significant operational upgrades.

The passing of Parlee’s eponymous founder, Bob Parlee, marked a profound shift—but not a conclusion. Instead, it clarified a responsibility: to carry forward the principles Bob established while building the organizational strength required to continue pushing the boundaries of performance. Under Harrison, Parlee is pairing Bob’s foundational mission with a more deliberate engine of R&D, new technical partnerships, and a rebuilt supply chain—collectively advancing the standard set decades ago.

Historically, Parlee has been an outlier in New England, a region where steel and titanium remain the inherited language of bicycle manufacturing—material echoes of an industrial past that once defined the area. Think Seven, Firefly, Richard Sachs, and a constellation of smaller builders, many fleeting, some enduring. Parlee belongs to this geography, but not entirely to its tradition. I see its presence in the same vein as the famed pizzamakers of Tokyo: practitioners working far from a craft’s perceived center, yet approaching it with an intensity and precision that turns distance into distinction.

Almost since inception, Parlee has been an if-you-know-you-know brand. I’ve encountered Parlee riders on the West Coast, in the UK, and on the Han River bike path in Seoul—only fractionally more here in Massachusetts. The bikes tend to attract a particular rider: fit, independent-thinking, quietly intense, professionally successful, and emotionally invested in the act of riding.

Bob Parlee was a high-performance boatbuilder and serious bike racer. Drawing on his knowledge of boatbuilding, he approached carbon fiber not as a path to ever-lower weight or ever-higher stiffness, but as a material capable of shaping comfort in service of performance. That idea—speed, durability, and volume reverse-engineered from feel—has always been the philosophical core of the company. In poetic terms, Parlees are designed to disappear beneath you as you ride them, a quality the brand’s following has affirmed to me repeatedly.

Carbon orientation at Parlee is tuned not exclusively for peak power, but for how a bike behaves after three or four hours in the saddle, on imperfect roads, and under sustained load. Performance is metered over duration rather than moments. In Parlee’s bespoke models, tube shapes, wall thicknesses, and layup schedules are adjusted deliberately for rider weight, use case, and intended ride style. Much of the artistry concentrates where the tubes meet—particularly around the bottom bracket and head tube—where forces converge and decisions compound.

Perhaps in a nuanced defiance of the region’s steel-and-titanium DNA, multiple members of the Parlee team described their take on carbon fiber manufacturing to me as closer to woodworking than metalworking: a process of layering and shaping rather than cutting to a fixed form. At these junctions, the layup becomes far more complex than along the tubes themselves, built up in multidirectional sequences that must reconcile forces arriving from multiple directions at once. Small changes compound quickly. In this context, the collective experience and longevity of the team read as essential to Parlee’s distinction—knowledge accumulated not in theory, but in hands, repetition, and instinctual judgment.

What has changed is not the foundation, but the intent with which it is now being extended. Parlee is pairing that depth of experience with a forward-facing posture defined by clear goals, deeper investment, and an explicit commitment to follow-through. The emphasis inside the company is on building deliberately toward what comes next: new products, new techniques, and new performance ceilings pursued with shared rigor. Today, Parlee feels less reflective than poised—its history intact, its future actively under construction.

New England is not kind to bicycles or their riders. The roads are scarred by freeze-thaw cycles. The weather is indifferent. Riding persists through winter because of a cultural refusal to let conditions dictate behavior. Cyclocross and gravel were practiced here long before they were named. Comfort, compliance, and durability are less lifestyle compromises than survival strategies.

Parlees reflect this reality without ornament. Tire clearances widened early. Disc brakes appeared before they were safe marketing bets. Compliance was prioritized while much of the industry chased stiffness curves. One gravel bike was named after Chebacco Road, a native-named frost-heaved test loop near the factory—less a branding abstraction than geography, weather, and spirit translated directly into engineering input.

Bob Parlee described himself as “an old Yankee”—thrifty with materials, suspicious of excess, focused on what lasts. That sensibility remains. So does the other side of New England intensity: restraint paired with ambition, spareness with curiosity. At Parlee, carbon fiber is still treated as a very much open question.

The six conversations that follow span leadership, engineering, sales, branding, and Parlee’s renowned paint operation. Taken together, they offer a composite view of the company as it looks ahead—revealing the multiple, interdependent components that shape Parlee’s future. If Parlee has a true differentiator, it isn’t any single frame, material choice, or technical decision, but the people who make the work possible. Under Harrison, that team is not simply maintaining what exists, but actively shaping what comes next—carrying the company forward while extending its relevance, reach, and performance into the future.

Chessin Gertler

John Harrison — Stewardship

“I didn’t come in thinking I was going to reinvent anything. What struck me immediately was that the problems weren’t about the product. The bikes were exceptional. The thinking was exceptional. The issues were operational—and those were things I understood and genuinely enjoyed working on. It felt like something worth protecting. Sitting here now, it’s almost impossible to imagine having done anything else.”

John Harrison is the owner and CEO of Parlee Cycles. With a background in enterprise technology and decades of experience stepping into complex businesses at moments of transition, Harrison came to Parlee not as an industry insider, but as a longtime Parlee rider who recognized both what the company already was—and what it could become. He acquired the brand during a period of financial and organizational strain, drawn equally by opportunity and obligation. Today, his focus is on strengthening the foundation beneath a culture of craft and performance that long predates his arrival, and positioning the company for a durable future.

What drew you to Parlee, and what brought you into this role?

Parlee was in Chapter 11 at the time. What became clear very quickly was that the problem wasn’t the product. The engineering, the fabrication, the brand—all of that was strong. The challenges were operational: inventory, purchasing, cash flow, channel development. Those were familiar problems to me, and ones I felt confident stepping into.

When I was deciding whether to get involved, I kept coming back to three questions. First, was my perception of the brand fair and complete? Second, were the right ingredients still in place to build something that could last another twenty-five years? And third, was I actually the right person to take that on?

The answer to the first question was overwhelmingly positive. Even in the first year after the acquisition, traveling to visit dealers and customers around the world was humbling. People told stories about how they ended up on their Parlee, how paint decisions were inspired by family history, how the bike became part of their life. The depth of attachment people have to these bikes is remarkable.

On the second question—whether the business could endure—what mattered most was still intact: the product, the engineering, and the people.

You keep returning to the team. Why was that so decisive?

One of the first things you notice is how long people have been here. The core group has been with the company for decades. For a small bike manufacturer that’s been through ups and downs, that kind of continuity is rare—and incredibly important.

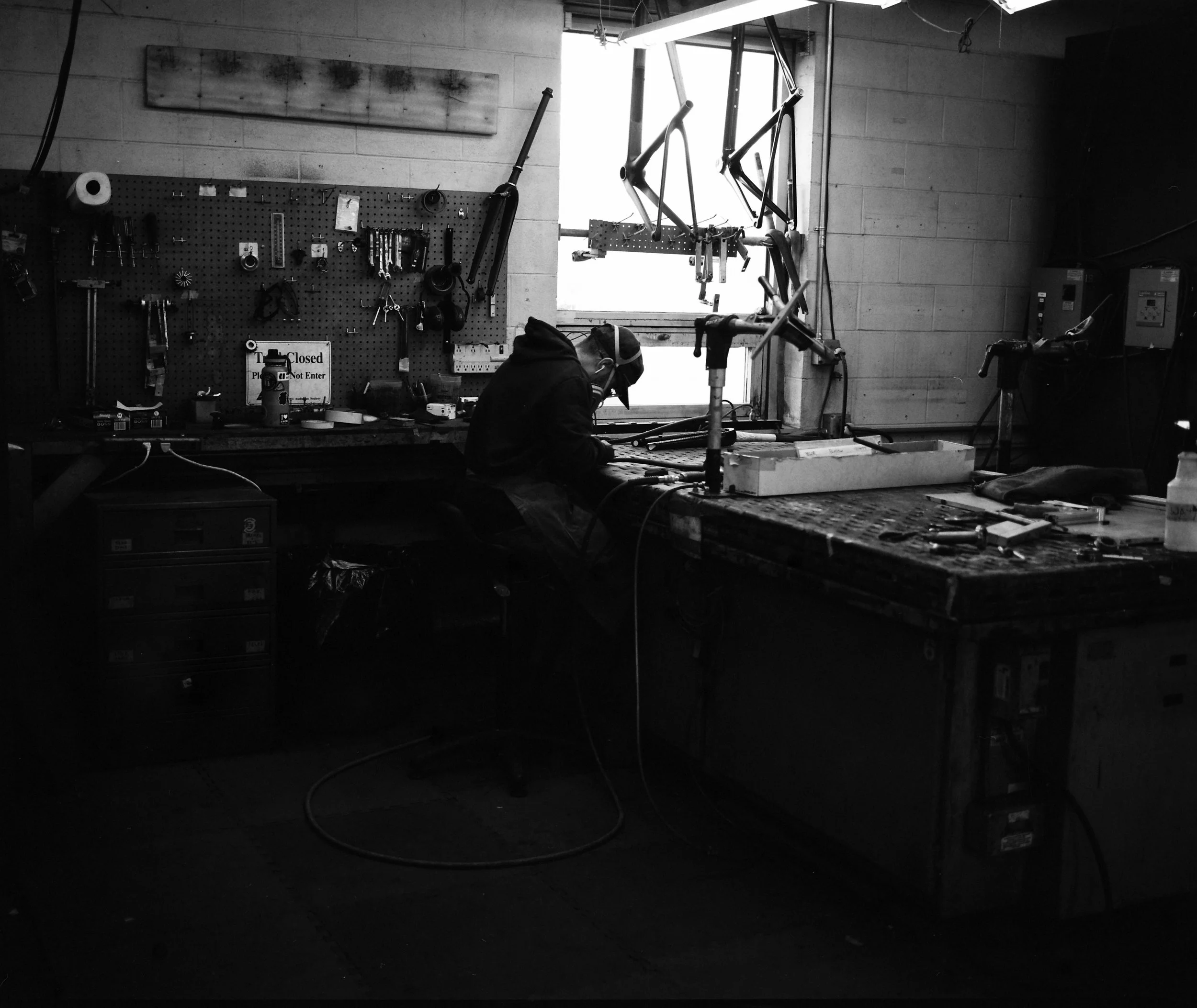

In craft-based work, experience lives in people’s hands. Rommel Mariano, our master builder, does the final assembly on frames that are built completely by hand here. After the tubes are fabricated and mitered, he hand-wraps all the joints using carbon fiber fabric—sometimes a hundred individual pieces just to seal the joints on a single frame. That’s a skill that takes years and years to develop.

Cody Haight, our master painter, has been here sixteen or seventeen years. Tom Rodi has been here about twenty. These people don’t just know how to do their jobs—they understand the technology, the engineering, and the history in a way that can’t be replicated.

At the same time, we’ve brought in newer perspectives. Lyndall Robinson, who leads manufacturing, joined about eight or nine years ago. She’s a trained carbon-fiber engineer and has introduced new thinking around layup development and process improvement. That combination—deep experience paired with fresh perspective—puts us in a very strong position going forward.

How do you think about Parlee’s future?

Parlee is a small player in the bike industry, and I expect it to remain that way. We’re not trying to be a mass-market brand. We’ll continue building bikes of exceptional quality, which means they’ll be priced accordingly, and we’ll continue serving the top end of the cycling enthusiast market.

That said, I do see us expanding the product range modestly and strengthening our dealer network globally. Today, we have regions where we’re very strong and others where there are clear gaps—even here in the U.S. Part of this next phase is making sure the brand is represented by the right partners, in the right places, with the right level of support.

The goal is a stable, sustainable business—selling a few thousand bikes a year. I don’t see us ever trying to build something that sells more than around 5,000 frames annually. That kind of scale would change what Parlee is, and that’s not the objective.

What should remain constant as the company evolves?

Bob started Parlee with a belief that carbon fiber could be used far better than it was at the time. Early carbon bikes were light, but they rode poorly. Drawing on his boatbuilding background, Bob understood how complex carbon layups could be used to control flex, vibration, and fatigue—to create a better ride experience.

That thinking led directly to the Z-series frames. The Z-Zero GT we produce today still carries very clear cues from the first Z bike developed twenty-five years ago. It’s the purest expression of Parlee: an uncompromised approach to engineering with a single goal of improving performance through comfort.

Bob also valued timeless aesthetics and was skeptical of trends that would age quickly. That sensibility remains. The forms are familiar—almost traditional—but they’re wrapped around the most advanced engineering we can develop. We push the envelope on carbon layups and finishes, but we don’t chase exaggerated shapes for their own sake.

What ultimately defines the Parlee ride?

Without question, it’s the ride experience.

Performance is a baseline expectation. The bike has to be fast—and ours are. But much of the industry has chased speed at the expense of everything else: connection to the road, vibration damping, how the bike feels after hours in the saddle.

We believe you can be just as fast without sacrificing those qualities. Comfort doesn’t mean softness or sluggishness. It means being able to ride hard for longer and finish feeling intact rather than pulled apart.

Technically, that’s achieved through extremely complex carbon-fiber layups. Many manufacturers use roughly 125 pieces of carbon in a frame. Ours use over 600, and the Z-Zero uses more than 1,000. That complexity allows us to tune behavior very precisely—where the frame flexes, how it absorbs vibration, how forces move through it—while still keeping weight down. It’s far more difficult to design and manufacture, but the result is something distinctly different and far more personal.

How do you reflect on the transition into this current chapter?

Bob’s illness played a significant role in the challenges the company faced, particularly during COVID. Despite that, the quality of the bikes and the way customers were treated never really suffered.

I think of myself less as an owner and more as a caretaker of this next phase. There will be someone after me, and someone after that. Parlee will continue because the core—the product and the people—matters. My responsibility is to make sure the company is strong enough, clear enough, and well-positioned enough to carry that forward.

Lyndall Robinson — Engineering & Design

“I don’t really think in terms of stiffness targets. I think about load paths—how forces move through the frame, how they change over time, and how the bike is going to feel hours into a ride, not just in a single moment. Carbon gives you the ability to tune that, but it’s not formulaic. It’s more like woodworking than metalworking. Small changes in orientation or layering compound very quickly, especially where the tubes meet. That’s where the real work is.”

Lyndall Robinson is Production Manager at Parlee. She works at the center of how the bikes are conceived, tuned, and ultimately brought into being. Trained as an industrial designer and engineer and deeply fluent in carbon fiber construction, Robinson translates abstract ideas about ride quality, durability, and performance into layups, junctions, and manufacturing decisions. Her work is less about hitting numbers than about shaping how a bike behaves over time, across conditions, and under real riders. In our conversation, she speaks of carbon fiber as a living material, the complexity hidden within frames, and the craft that goes into making a Parlee.

Can you introduce your background and how you found your way to Parlee?

I went to the University of Kansas for industrial design. I studied abroad in Australia, came back, and school just didn’t feel the same. I ended up running a Kickstarter in Alabama building bicycles—carbon, bamboo, fiberglass—and that became my last year of school instead of being a traditional student. It was under an umbrella called Hero Bike.

I ran a few Kickstarter projects through there—two bicycles, a couple different skateboards—and focused a lot on different ways of manufacturing. That was my first real dive into carbon fiber and bicycles. After that, I built my own bike, and I got picked up by Parlee Cycles and moved out here.

What’s your role at Parlee?

Overall, I’d describe it as operations and fabrication management. I facilitate orders through the entire custom factory process—everything from the carbon build, to paint and then out the door. I’m also very involved in engineering the carbon fiber layups and I still build parts. Every bike that goes out is touched by me at some point.

Where do you see Bob’s legacy showing up most clearly right now?

The new GT fork, honestly. As a technology piece, building forks for the new GTs here is a pretty big feat for us. And I have to personally say I took a lot of what Bob taught me and transcribed it into how I make the fork.

Bob did a lot of layup design for typical round tubes, and I worked a lot with him on that. So I took knowledge we developed together and implemented it into the fork. And then there’s his testing process—iteration, and just keeping going.

The layup has over 180 pieces. Compared to something like a top tube—your top tube has 8 to 12. So you can think about how many different directions that is, and how much that changes ride quality and dampening.We built 25 different forks, tested all of them, and tried to understand what was going to ride the best. It was quite the process.

What is the guiding principle when you’re engineering these parts?

Comfort is king or queen. And then from there, the ability to fit so many different types of people on this bike. Our process is so different from other companies, we have the capability to build the bike that is going to fit you, no matter what.

How bespoke is the bespoke process, really? If someone orders a GT, what changes?

It’s hugely bespoke. Everything from working with the dealer, getting a fit, choosing paint or not—it’s completely bespoke. It’s a long process, but everybody gets their dream bike in the end.

We’re looking at rider weight and fit, and then what the rider wants to do. Gravel riding, road riding going fast, endurance and leisurely rides—there are so many different things. We have a tube set for each different kind, based on height and weight. Even the way we put all the tubes together.

If you want something specific—like a really stiff bottom bracket—we can make a stiffer bottom bracket for you in our molding process.

We’re hoping that from the time I get the order from the dealer, it’s like 60 to 90 days. And as far as a custom bike goes, that’s exceptional—especially given we’re building everything: the fork, the tubes, the derailleur clamps. We’re building all of it in-house here.

How big is Parlee right now?

We have twelve people.

From a materials and manufacturing standpoint, how do you actually build these bikes?

Everything we use is prepreg. I try extremely hard to never do wet layup. It creates messes. We’ve done it on many different things, but resin gets everywhere.

We use prepreg, and we have four different types of carbon fiber that we’ll probably put in every single tube—different directions, obviously. We have our Automatrix, which is a huge lifesaver. It cuts out all the pieces instead of us hand cutting everything, which we were doing. We were probably doing that like seven years ago. It was horrible.

The thing that really differentiates our ability to make such a custom bike down to the millimeter is our molding process after the tubes are made.

The whole bike is carbon fiber. We’re not even putting any inserts in besides the rivnuts for the bottle cages at this point, which is pretty unheard of. Now that we have direct mount, there’s no inserts in the dropouts.

And our molding process—there’s no glue, there’s no foam. It’s literally just carbon on carbon. That’s what makes the ride quality so great. It’s one of the reasons, of course. But we can get down to the millimeter, and that’s kind of our technology.

How do you feel Parlee’s place in Beverly and New England more broadly, shape the brand?

Resilience. I feel like a lot of people around here are resilient, and Parlee Cycles has been resilient.

We base everything on really hard work—extra time, making something perfect for a customer. And Bob and Isabel keeping all of us here for so long, still making bikes. It’s pretty neat.

And there’s a different riding culture up in New England. They ride through the winter. They’re rugged. It’s definitely different than where I’m from.

How long did you work with Bob before he passed?

About ten years.

What do you see as his legacy inside Parlee?

Within the business, he has a huge legacy as kind of one of the forefathers of carbon fiber bikes. He was doing it in a way that was so different from everybody else for so long.

Small businesses are hard, but it gave us such a foundation to work from. It was just because he wanted a new bike that felt better than everybody else’s. He couldn’t get what he wanted, so we made it.

And I think that’s what we hope our customers are coming to Parlee for. They can’t get what they want anywhere else.

He was also a problem solver. And I think Parlee Cycles—we’re really good problem solvers, especially in fabrication. We can figure out how to make almost anything. That’s a direct correlation from Bob and his legacy.

Can you give an example of that problem-solving mindset in action?

We built a bike for a really big NFL player—around 6'8", like 380 pounds. The tubeset needed to be able to hold a huge load.

And at the same time, we were building a bike for a woman who was 4'11". We were literally able to put her frame through his.

We had to make sure the layups were correct. That’s the work—problem solving those situations. We’ve made step-through bikes before when someone needs them. You can pretty much make anything in carbon fiber if you spend enough time figuring it out.

What has it been like inside the company since Bob’s passing?

It’s a huge hole. For a lot of us who were here for a long time.

Bob and Isabel were great. They took everybody in like family. Me personally moving across the country and not knowing anybody—they filled a big void there.

I miss him when I am working on my fork.

What has changed in the work since he’s been gone?

It’s funny, because we still do a lot of things the way that he would. We all learned carbon fiber from him. We’re essentially continuing his legacy.

But there were a ton of things in that last year—like the fork, thinking about handlebars and stems—ideas we had been talking about with him for years, and we’ve just been able to implement them now.

Technology has changed, so we’ve had to adapt—direct mount, new chainstay for the GT.

And we introduced bikes that we’re making in Portugal in that time period.

How do you think about the Portugal-produced bikes in relation to the bespoke bikes made here in Beverly?

The Ouray and the Taos are being produced in Portugal. They’re not entry level, but they’re not bespoke in the way the custom bikes are.

We still do some customization because we have the capabilities here—finishes, and we have a pretty good size range. And we also do customization on crank length, stem, handlebar, setback seatpost—stuff like that. Dealers can order them in a way that’s more tailored. But the sizing is standard—extra small through extra large.

Does the vibe of the company feel different now?

I’d say 50/50. There’s definitely a new vibe when new people come in. Priorities change—stock bikes, custom bikes, trying to mesh those together, what’s best for the company.

But the underlying goal to create the best bikes is still the goal.

You have a lot of responsibility here, and you’re also one of the few women in this kind of role. Do you think about that much?

It depends. Here, I’m pretty ingrained in the system, so it doesn’t really cross my mind day to day. There are situations where you notice it more—if someone doesn’t know who I am yet and I’m at a shop or something. But it shifts once people know.

What are your goals going forward—personally, and for Parlee?

For the brand: continue to improve our process. I always want to innovate what we already have. I’d love to come up with new custom bikes, start making handlebars, stems—build the company so that it’s more like us, and we’re not getting all this other componentry from other people. It would be really cool to do that.

Personally, I want to work more on the fork. It’s passing everything, but you always want to make it lighter. And when I make my personal bike, what can I do there? How can I take what I want for myself and implement it into what other people might want?

That’s one of the neat things about the fabrication team. We always think of things we want to try on our bikes first. And if it’s really cool and makes the bike different, we start to offer it for customers and improve everything all the time.

That’s where the whole company started. That’s the legacy.

Tom Rodi — Engineering & Product

“Bob and I sat down and tried to break comfort into measurable components—vibration, fatigue, deflection, frequency response. I think we ended up with something like twenty-five different indicators, and even then it felt incomplete. We argued about it. We kept adding things. Eventually it kind of collapsed under its own weight. Not because comfort isn’t real, but because it’s experiential. You know it when you ride it. And if you design around that long enough, you start to trust feel as much as data.”

Tom Rodi has been with Parlee for more than two decades in a variety of roles. He worked alongside Bob Parlee through the company’s formative years and remains deeply involved in how Parlee frames are conceived, evaluated, and evolved. Rodi’s perspective is shaped by long exposure—to materials, to riders, and to the slow feedback loops that reveal themselves over years of experience. Where others speak about performance in snapshots, Rodi thinks in timelines. In our conversation he reflects on comfort as a measurable but stubbornly elusive dimension of performance, and on the difficulty of reducing embodied experience to numbers.

Can you introduce your background and the path that brought you to Parlee?

I’ve been with Parlee since 2003. I worked in bike shops all through college to pay my way. I didn’t have money for nice bikes, so I worked on my own. Eventually I got this crazy idea that I was going to make my own frame. I was lucky—I had an art professor who indulged that idea as an independent study. He was a painter, but he loved mechanical things, had an old Bugatti, had bought a handmade steel bike decades earlier. He understood craft.

After school, I didn’t really know what to do. In the mid-’90s it felt like all the bike industry was in Europe, Colorado, or California. I ended up working in tech for six or seven years, which is how I landed in Massachusetts, working out in Hopkinton in data storage.

But even then, I was still making bikes. Nights, weekends—I had a shop in my basement. I was welding, brazing, taking machining and welding classes, learning CAD. After 9/11, the tech bubble burst, and around 2002–2003 my wife and I took some time off. I decided I was going to hang out my own shingle and build steel bikes.

That was a hard time. Steel bikes were really dying then—this was before the handbuilt renaissance. I was trying to build bikes, sell them, do everything myself. My wife finally said, very wisely, “You should go work with someone who’s already building bikes.”

I had heard about this guy in Peabody—Bob Parlee. I knew he’d built bikes for Tyler Hamilton, but that was about it. I saw an ad that they were looking for part-time help. I came up, started working part-time, and that was it.

Was there a moment when you knew Parlee was different?

Completely. The first time Bob explained what he was doing, and then I rode one of the bikes—it was like that Indiana Jones moment when they open the Ark, or the suitcase in Pulp Fiction. I’d ridden a lot of early carbon bikes and honestly didn’t think much of most of them.

That ride felt like seeing the future. I realized immediately that steel—what I had been romanticizing—wasn’t the whole story anymore.

What was different about that ride compared to other bikes you knew?

At the time, you kind of had trade-offs. Aluminum bikes were stiff and fast on smooth roads, but brutal the moment the pavement got bad. Steel and titanium had comfort and liveliness, but you gave up weight and stiffness.

Bob’s bikes somehow ticked all those boxes. Light like carbon. Stiff where you wanted it. Comfortable and lively like steel. It felt impossible. And they were still significantly lighter than anything comparable at the time.

That was the “trifecta” moment for me. I’d ridden enough bikes to know that wasn’t normal.

How did Bob achieve that when early carbon bikes often didn’t necessarily ride well?

A lot of early carbon was what Bob used to call “black aluminum.” Light, but generic. The layups were simplistic—mostly fibers at 0 and 90 degrees, very little off-axis fiber. That gives you a stiff structure, but not a nuanced one.

With composites, you’re literally making your own tubes from nothing. Even if two people start with the same roll of carbon and the same mold, they’ll build completely different tubes depending on how they place the layers. Down tubes, top tubes, stays—they all want to do different jobs.

Bob was one of the first to really lean into that. He also pushed tube diameters up—larger tubes with thinner walls—which was closer to aluminum sizing, but applied thoughtfully with carbon. That combination mattered a lot.

And then there’s how the tubes are joined. That joining technique—how loads flow through the joints—has evolved over 25 years, but it’s still fundamentally different from most of the industry.

People used to say things like, “This carbon bike reminds me of my steel bike.” That was huge for us. Comfort, liveliness, and still better climbing performance and much lower weight.

Comfort keeps coming up. Why is it so central to Parlee?

Because roads haven’t gotten any better in the last 25 years. Comfort isn’t the opposite of performance—it enables it.

If you can give comfort without taking away stiffness, handling, or weight, what’s the downside? You stay fresher longer. You maintain power. You keep control on real roads, not just perfect pavement.

How much does New England influence that philosophy?

A lot. The roads alone will teach you some lessons.

Cyclocross was huge here early on. We were riding ‘cross bikes on the road and off-road 20 years ago—long before “gravel” was a word. Weather matters too. We built our first disc brake road bike around 2012, years before it was mainstream, because riding in wet conditions on rim brakes just isn’t great.

There’s also a kind of New England—or Yankee—ethos. Bob used to joke about being a “tight Yankee.” There’s a thoughtfulness about material use, efficiency, not being wasteful. We care about transitions, about not doing things just because we can mold any shape we want.

Bob looms large in Parlee’s story. How do you think about his legacy?

Bob would be the first to tell you it was never just him. His name is on the down tube because he had the chutzpah to start the company, but it was always a team.

Early on, Bob realized he wasn’t best suited to repetitive frame production. He was a tinkerer, a problem solver. He delegated to people who could execute consistently. And he always gave credit.

What I took from him was a willingness to question dogma. Road cycling is incredibly resistant to change. I remember when STI levers were heresy. When people said disc brakes would never belong on road bikes. When clinchers were considered unacceptable for racing.

Bob always asked, “Why not try it?” We still have a corner of the shop full of failed experiments. Tri bikes with no top tube. Test mules that never went anywhere. But bikes are small enough that you can try things. On Monday you have an idea; by Tuesday afternoon you can be riding it.

That experimentation—that curiosity—is a huge part of his legacy.

Your role has evolved a lot over the years. What do you focus on now?

When I started, I worked directly with Bob on fabrication and design—making frames, evolving manufacturing processes.

Around 2006–2007, Bob and Isabel asked me to focus more on the business side. I had experience in tech sales and channel development, and I’d worked in bike shops. So I spent about ten years building the dealer network, expanding distribution internationally, while still contributing to product work.

Around 2017, once the business was more stable, I shifted back toward product management. We started offering complete bikes, not just frames. Today, my role is essentially head of product.

That means managing the entire product lifecycle—what markets we’re in, what bikes we should make, design and concepting, supplier relationships, down to screws and washers. One day I’m sketching a product, the next I’m working with a supplier on a fastener.

It’s a small company, so I still do dealer work, marketing outreach, trade shows. I’m in London for Rouleur Live. Being out there talking to riders and dealers informs the product. You can’t design in a vacuum.

What does the future of Parlee look like in this new chapter?

The vision hasn’t really changed: make fantastic bikes.

One big shift has been moving stock bike production from Asia to Portugal. That wasn’t about tariffs—it was about quality and workflow. As a small company, you’re a small fish in a big pond in Asia. Factories are optimized for price, not the kind of standard we care about.

In Portugal, we’re working in a single-piece workflow, with monthly shipments—much closer to how we operate here in Massachusetts. It lets us manage inventory better and serve dealers more reliably.

John’s leadership has been huge here. He brings deep experience in sales, marketing, operations, logistics, and technology. Bob and Isabel carved out an incredible brand without that background, which is amazing. But having that operational rigor now allows us to focus on what we love—product—without the business side constantly being on fire.

We don’t want to be Trek or Specialized. There’s a wide-open lane for high-end, high-performance carbon bikes focused on quality and personalization. Our job is just to keep making good stuff.

What keeps you excited after all these years?

Bikes are still small enough that you can try things. You can touch the material. You can ride the result.

The best products come from passion. If you care deeply about what you’re making, that shows up in the result. That’s what’s kept me here for over twenty years—and why it still feels worth doing.

Nate Plant — Sales & Relations

“There’s a hallmark ride quality that I usually describe as quiet. The bike disappears underneath you. You’re not thinking about noises or harshness or what the bike is doing—you’re just riding. What’s important is that this feel carries across the entire lineup. A Z1 rides like a Z5 rides like an RZ7. We work really hard to maintain that consistency. When we launched the RZ7, I had a longtime partner tell me—almost emotionally—that it rode like his Z-Zero. That meant everything to us.”

Nate Plant is Parlee’s Regional Sales Manager, overseeing the East Coast as well as Europe and the UK. Before joining Parlee, Plant ran a Boston-area bike shop that was itself a longtime Parlee dealer, giving him years of firsthand experience selling, fitting, and riding Parlees. He has spent nearly a decade at the company, bridging the internal culture of the factory with the external realities of the market. From dealer selection to customer education, Plant’s role hinges on translating Parlee’s values into relationships rather than volume. He speaks candidly about ride quality, brand mystique, and why Parlee would rather be small and understood than everywhere.

Can you start by explaining your role at Parlee and how sales is structured?

I’m one of two regional sales managers. Cary Tatro handles the western U.S., Australia, and Asia. I cover everything east of the Mississippi, plus the UK and Europe. We joke that our territories are hemispheres. That’s kind of a theme you’ll hear from everyone here—we’re small, and we’ve always been small. We’re used to that, and at this point we wouldn’t want it any other way.

How do you think about where Parlee shows up in the world? Is the goal broad coverage or something more selective?

It’s always been organic. We do target certain markets when it makes sense, but we’ve always been very particular about who we work with. Sometimes, honestly, we’d rather do without than partner with someone who doesn’t really represent the brand.

Because we’re small, we rely heavily on our partners to tell our story—to recommend Parlee, to educate customers. We don’t have the marketing horsepower where people just walk in asking for the bike because they saw it win the Tour or because it’s everywhere on Instagram. That means a shop has to want to be an advisor, not just a retailer leaning on hype.

Parlee is the original fit- and ride-quality-forward brand. How does that land in today’s market, where everyone claims comfort and performance?

When Bob started the company 25 years ago, carbon bikes were light and stiff and pretty miserable to ride. That was our starting point: ride quality first.

Now, everyone says their bikes ride well. Everyone says they fit well. So we have to go a step further and explain why our bikes do—what’s actually happening structurally and materially. There are technical reasons for it. It’s not just marketing language.

Our bikes are meant to grow with you as a rider. That’s something that’s hard to explain quickly, but it matters a lot over time.

How long have you been at Parlee, and what was your relationship to the brand before that?

I’m into my ninth year now—I started in the fall of 2017. Before that, I ran a shop just outside Boston for about eight years, and we were a Parlee dealer. So I knew Bob and Isabel, Tom, Rommel, Lyndall—all of them—from that side of the counter.

When the opportunity came up to join the company, I took it and haven’t looked back.

How has the company changed since Bob’s passing and with new ownership?

In terms of principles, goals, and product philosophy—very little. Operationally, a lot.

Bob and Isabel weren’t just founders; they were like parents to a lot of us. But that didn’t always mean we were dialed operationally.

With John coming in, there’s been a huge step forward in systems—IT infrastructure, procurement, logistics, organization. It’s allowed us to be better at what we were already trying to do. And the transition itself was incredibly organic. John was a customer. I sold him a bike years ago. Bob was still deeply involved right up until the end—there was a design meeting two weeks before he passed.

This kind of transition doesn’t usually go well in cycling. For us, it really has been a fairytale.

Bob’s illness lasted several years. How did that period affect the company internally?

It was about four or five years. He told the team around late 2020 or early 2021. We’d encouraged him to share it—we wanted him to feel the love and support from the people he’d influenced—but that wasn’t his style. He always called himself an old Yankee. He just wanted to keep working.

He ran the business through bankruptcy and through the pandemic while he was very sick. After he passed, the outpouring from the industry was overwhelming. People we didn’t even realize he’d influenced reached out. That legacy hits differently now. When we release a new product, it’s not just another bike—it’s an extension of what he started.

In your words, what makes a Parlee a Parlee?

The way they ride. That’s the simplest answer.

There’s a hallmark ride quality that I usually describe as quiet. The bike disappears underneath you. You’re not thinking about noises or harshness or what the bike is doing—you’re just riding.

What’s important is that this feel carries across the entire lineup. A Z1 rides like a Z5 rides like an RZ7. We work really hard to maintain that consistency. When we launched the RZ7, I had a longtime partner tell me—almost emotionally—that it rode like his Z-Zero. That meant everything to us.

How would you describe the internal culture that supports that outcome?

It sounds cheesy, but it’s a family. It really is.

For over 20 years, it literally was a family business. And now, we’re in a place where there aren't any passengers. There aren’t transplants cycling through brands. The core team has been here forever. Rommel and Tom are essentially employees three and four. People stayed through Chapter 11. Nobody looked for other jobs. We just said, “This has to work.”

That loyalty isn’t strategic—it’s instinctive. We look out for each other. We’re transparent. Everyone understands what everyone else does, even if we can’t do it ourselves. That empathy makes a huge difference.

How does Parlee’s New England location factor into all of this?

The roads, first of all. That informs everything.

Chebacco—the gravel bike—that’s literally named after the frost-heaved gravel road between Tom’s house and the factory. That was our test loop. These aren’t abstractions.

There’s also a blue-collar, old-Yankee sensibility. Thoughtfulness with materials. Efficiency. No pretense. The building itself is an old railroad turnstile. Where the train spun around is now the paint booth. It’s not a showroom—it’s a working factory.

We like it that way.

From a sales and brand perspective, how are you positioning Parlee today?

We’re learning to be more unapologetic. There are off-the-shelf bikes selling for $17,000, $18,000, $19,000 now. If someone is willing to spend that, why not consider a bike made specifically for you?

We’ve also shifted language. “Custom” can feel intimidating. We talk more about “bespoke” or “made-to-measure.” These bikes aren’t just for very tall or very short people—they’re for anyone who wants something with soul and personality.

The product always comes first. We’ll market it, but we won’t compromise it. We’re terrified of becoming a brand that just licenses its name. That will never happen here.

If there’s one thing you hope people understand about Parlee, what is it?

That we care. Deeply.

There are twelve of us. Everything that leaves the building is personal. If something isn’t right, people stay late to fix it. That matters when you’re asking someone to trust you with a bike at this level.

Sarah Vogel — Brand & Communication

“Parlee has never been accessible to everyone from a price standpoint. I don’t think that’s a negative. It’s a byproduct of an uncompromising standard of quality. We use cost-no-option methods, take time, pay attention to every detail, and pursue a sublime ride experience. A perfect carbon finish off the line. And we still do true custom—built around someone’s fit geometry. Parlee is already a dream bike for a lot of people, but it’s not common knowledge. It’s still “if you know, you know.” We want people to know.”

Sarah Vogel is Parlee’s Marketing Manager, joining the company amid a broader effort to clarify and articulate what Parlee stands for. With prior experience at Specialized across both retail and corporate roles, Vogel brings a rare mix of industry fluency and community-focused brand thinking. At Parlee, she is tasked with building the company’s first cohesive brand framework—one that honors its history without being defined solely by it. Her work centers on reframing comfort as performance and translating a deeply experiential product into language without flattening its nuance. In our conversation, Vogel discusses the challenge of making an “if-you-know-you-know” brand legible without compromising what makes it special.

Let’s start with your role—what did you come to Parlee to do?

I joined Parlee in August. It feels like it’s been a lot longer—in a good way. I’m the marketing manager, which means I do pretty much everything: social media, the backend, and what we’ve been working on most intensely—reimagining the overall brand and how we talk about each product.

I came from Specialized in Colorado. I worked retail, then at their corporate office in Boulder doing brand experience—community engagement, local marketing. After moving back to Massachusetts I spent some time in fundraising, but I couldn’t stay away from bikes.

When you arrived, were you inheriting something established, or building from scratch?

A bit of both, but mostly from scratch. Since John took over, pieces of marketing had been handled by freelancers, so there was some foundation. But the big work—core pillars, messaging, rebrand-level clarity across the line—that’s essentially new.

What’s the core problem you’re trying to solve with this brand work?

Communication. Consistency. And awareness.

When someone comes to our website—or hears the name Parlee—we want it to be immediately clear what we stand for. Right now, there isn’t a lot of brand awareness, and even when people have heard of Parlee, it’s not always clear what Parlee is, or why it matters. The goal is consistent messaging across the product line, and across dealers, and across every touchpoint—so someone can actually align with the brand.

Ideally, I want an immediate association: Parlee makes the best bikes in the world.

How are you structuring that messaging? What are the pillars?

We’re still in the process of finalizing, but the core pillars are: Innovation, Experience, Comfort, Craftsmanship, and possibly a fifth: People/Relationships

We’re debating whether we keep it to four or allow five, because relationships really are a major part of Parlee.

Can you unpack those pillars a bit?

Innovation is our engineering—25 years of custom fit data, and the way we build carbon. Our layup is far more intricate than most brands because we prioritize the rider experience above everything.

Experience is the “mysterious sauce.” People ride a lot of bikes and think, “Yeah, it’s a bike.” Then they ride a Parlee and finish the ride almost baffled—like, what just happened? Why did that feel so different? Why did that ride feel better than anything else I’ve ridden?

Comfort is a huge part of that. Our bikes are insanely comfortable. You don’t feel as beat up. You finish your ride and you still feel like a person—your shoulders don’t hurt, you’re not wrecked. It’s kind of crazy.

And craftsmanship: everything is handmade. Even the bikes made in Portugal—the production-line bikes—are still made by hand by our manufacturer. It shows up in the quality and attention to detail. You can feel it when you ride them. They ride like a Parlee.

What does success look like for you? Is this about sales, or something else?

Sales matter, obviously—but the primary goal is to improve how we communicate. A clear framework helps us shape product messaging so each bike is an embodiment of the pillars. It makes us coherent—internally and externally.

And it helps solve a real issue: people don’t know Parlee exists, and even if they do, they don’t necessarily know what it stands for.

When you did your initial deep dive on Parlee, how much of the brand was “Bob Parlee,” and how much was the company?

Right now, they’re not very separate. Our website messaging is very focused on Bob Parlee. And of course we want to include the history—this company wouldn’t exist without him. He was a genius in carbon fiber, and he set the foundation for everything.

But defining Parlee as a brand separate from the person is part of what we’re doing. The brand has to stand on its own, anchored in what the company is now—this small team, this collective expertise, the way the bikes are built.

So in a sense, this is about revealing what’s already true—but hasn’t been articulated outwardly.

Yes. I think the lack of that separation—of a clear outward definition of what Parlee stands for beyond Bob—contributed to Parlee being “lost” in a way.

The good part is: we’re small enough that everyone can contribute. We’re having a real internal conversation about what Parlee means, from different perspectives—design, production, sales—and condensing it into something that feels true to the people who make up Parlee.

If this works—fully—what does Parlee look like in five or ten years?

A dream bike brand—widely understood as one.

Parlee has never been accessible to everyone from a price standpoint. I don’t think that’s a negative. It’s a byproduct of an uncompromising standard of quality. We use cost-no-option methods, take time, pay attention to every detail, and pursue a sublime ride experience. A perfect carbon finish off the line. And we still do true custom—built around someone’s fit geometry.

Parlee is already a dream bike for a lot of people, but it’s not common knowledge. It’s still “if you know, you know.” We want people to know.

You’re trying to reframe comfort as performance. Why is that hard in cycling right now?

Because “comfort” became a bad word. People hear it and think of cruisers—upright beach bikes. But comfort should mean maximizing your potential as a rider: more distance, more speed, more volume, more enjoyment. Most people are not WorldTour riders. They don’t need a brutally stiff aero bike. They need something that works on real roads.

Tom said something the other day about the Ouray—our all-road bike—that stuck with me: “For real roads and real people.” That’s exactly it. A compliant frame, wide tire clearance, potholes that feel smaller. Comfort becomes performance for everyone. If your bike isn’t comfortable, you’re not going to want to ride it.

Do you have a personal reference point for how dramatic the difference is?

Yes. I’ve ridden the highest-end bikes from the big brands. My favorite bike I’d ever ridden was an S-Works Tarmac. Then I rode an RZ7 for the first time and I was genuinely shocked. It blows it out of the water.

And the crazy part is: nobody knows.

If the product experience is that strong, what makes it hard to communicate?

It’s nebulous. It’s subjective. It’s hard to quantify.

Tom has a story about this: he and Bob tried to distill “comfort” into measurable components—like, how do you say a bike is X percent more comfortable? They got to something like 25 indicators and it still didn’t cover it. They argued about it, and it kind of became a wash because it’s hard to categorize comfort in a concrete way.

That’s one of the challenges: the experience of riding a Parlee is so significant, but putting it into words—without it becoming vague marketing—is hard.

What do you want to change about who feels invited into Parlee?

I think Parlees have been perceived for a long time as almost too expensive—so people automatically discount them. “That’s not for me.” We don’t want to apologize for quality, and we won’t compromise. That’s completely contrary to who we are.

But we do want people to see someone who looks like them on a Parlee and think: maybe this bike is for me.

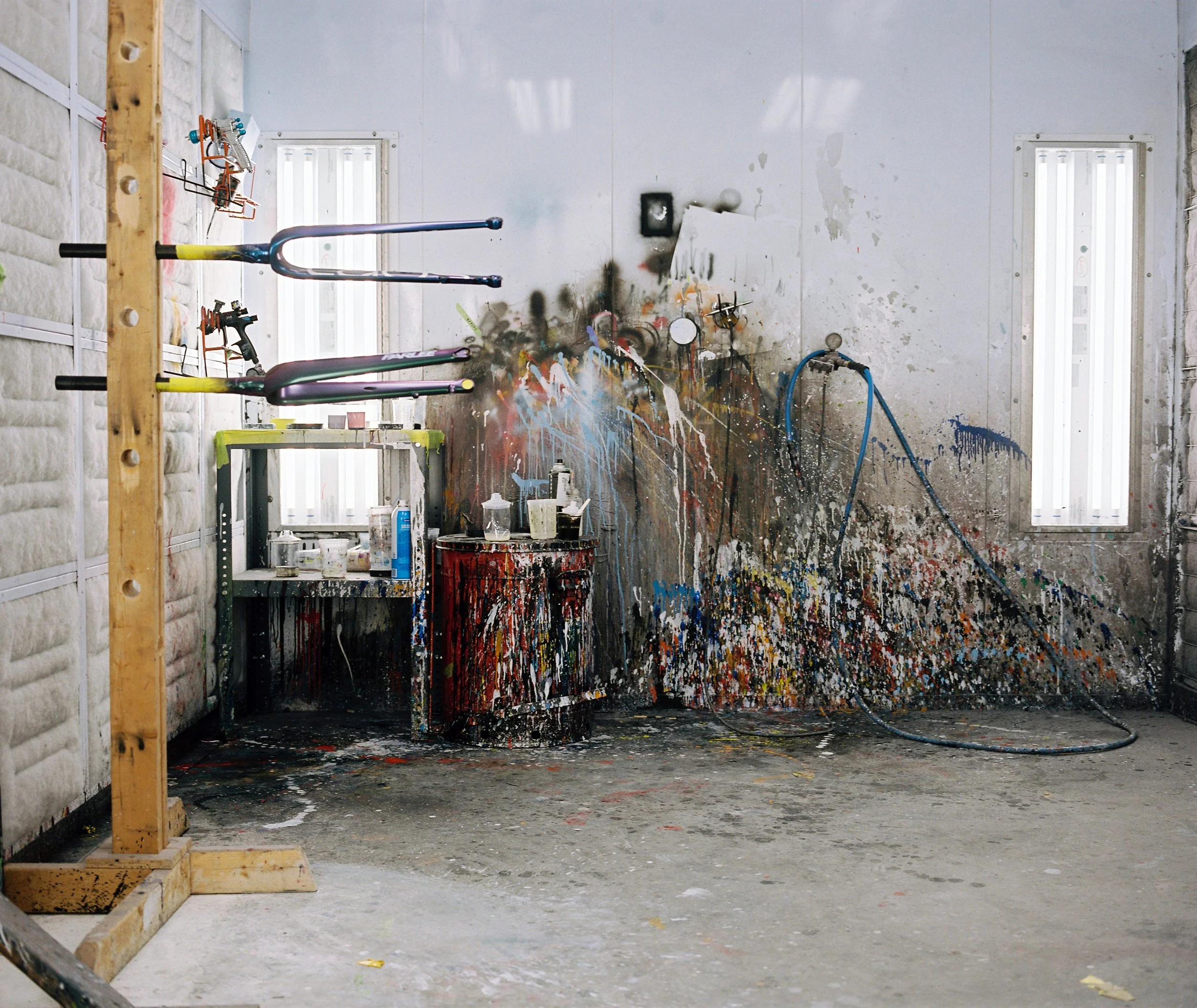

Cody Haight — Paint

“This is very much a dream job. We’ve always offered full custom paint straight from the factory—whatever your heart desires. Very rarely do we tell someone no. When I see one of my bikes out in the world, it’s still kind of surreal. Bob and Isabel built something that felt like a family, and everyone here is just happy to carry that forward.”

Cody Haight is Parlee’s painter and one of the longest-serving members of the team. He joined the company in 2010 straight out of high school. Haight is responsible for Parlee’s factory-direct custom paint—an increasingly rare offering that allows customers to engage directly with the final expression of their bike. In our conversation, Haight reflects on process, pride, and what it means to spend a decade and a half at Parlee.

Your role and what brought you to Parlee?

My name is Cody Haight. I’ve been the painter at Parlee for 16 years now. I got the job while I was still a senior in high school doing collision repair. A lot of the painters came from there. They went back looking for a new painter, plucked me out of high school, and I’ve been here ever since. I’d probably say I’m the third longest one here. I think Tom and Rommel—the bike builder—are one and two.

Your background was auto painting and collision repair. How does that translate to bikes?

A lot of the paint techniques transferred over. It’s a different beast doing custom work versus matching colors, but that’s why I got into bicycles instead of staying in cars. I like the custom aspect. I enjoy doing the fun paint jobs.

When I first started, I was taught by my manager, Brian Burke. Before he left, he had been here around 13 or 14 years. So I had a very experienced painter teaching me as I came in.

When I first started, the custom paint jobs weren’t as crazy. They’ve gotten crazier and crazier over the years as people learned what we can do.

Do you feel like the custom paint world is competitive? Trends? Technique?

It follows trends. A couple years ago everyone was all about neon. Now it’s more subtle—lots of blues. When COVID happened, people took time and came up with crazy ideas for us to paint. During the shutdown we did a lot of honeycomb paint jobs, a lot of masking.

Walk me through the Parlee process. If I order a bike with custom paint, what happens—from order to delivery, specifically your part?

It depends on the option, but typically if it’s a ZZero: I get it from Rommel and Lyndall upstairs—sanded and prepped—after the customer talks to Nate or Cary.

Then I receive the frame and put down a base layer to make sure everything’s good. I work off a paint render from one of our designers. They work with the sales guy to make sure everything’s right. I’m always around to check things, talk through it, make sure it works in real life.

From there it’s building up the files on my computer—logos, placement, everything how it needs to be—then we start painting. That’s when the fun starts.

In the paint process itself, where does the time really go?

Honestly, painting is usually the least amount of time I spend. Most of it is masking and measuring and making sure everything’s right. Actually spraying paint is the smallest part.

What’s distinct about Parlee’s approach to paint?

Since I started here, we’ve always offered full custom paint from the factory—whatever your heart desires. We very rarely tell someone no, unless it’s copyright or something that can’t be done.

We’re definitely one of the few—if not the only—brands where straight from the factory you can get your bike fully custom. And I think that’s always resonated with Parlee: it’s for the customer fully.

Do you meet customers? Do you ever see your work in the wild?

I run into people around town riding bikes I painted and we’ll have a conversation. It’s pretty amazing.

It’s funny—my fiancé gets shocked to see I have fans and that people know my work.

Any memorable paint jobs—favorite, wildest, most insane?

Back in the day my manager used to warn me: never paint samples you wouldn’t want to paint on an actual bike.

I didn’t listen. I ended up having to airbrush like 10,000 squares on a bike because I thought it was a good idea. I really liked it, but I would not want to do that paint job again.

What are you excited about right now—technically, aesthetically, product-wise?

In the last year, having the new Ouray and Taos be raw carbon—that makes me really excited. It opens up paint possibilities.

And the GT work has been amazing. When I started it was all mechanical and external routed bikes. Now it’s internal routing, Di2. It’s nice not dealing with cable routing around paint jobs. It gives you more freedom—like honeycomb. You don’t have to wrap patterns around external routing; you can get a smoother finish. It’s fascinating to see the leaps.

I remember when Parlee made a Prius bike years ago—we were on Good Morning America—because you could shift gears with your mind! So yeah, it’s been amazing seeing how everything progresses.

Raw carbon as a canvas—what does it enable, and what does it demand?

If we’re showing carbon, if there’s anything wrong with it, you really can’t hide it. But it gives you opportunities too: clear coat it and let the carbon show, or hit it with a candy—like candy blue—so you still see the weave but with a tint.

And honestly, even raw carbon with no paint—it looks amazing. It shows off our work. It helps show off all the hard work everyone puts into it.

You’re a North Shore guy. Does it mean anything to be doing this here—Massachusetts—where these bikes are made?

Yeah. This is very much a dream job. I enjoy knowing people are out there riding my bikes.

I have a hard time calling myself an artist, but a lot of people consider me one. That’s a weird disconnect. I was never the best art student. But I took to painting, and I’ve always loved the custom paint world. Put a paintbrush in my hand and I’m not very good. But this—this I love.

What’s the team dynamic like? What’s special about the group?

It’s always been great. Bob and Isabel were amazing to work with. They never made you feel anything less than family.

We’ve carried that mentality: you come to work at Parlee, you become one of us. Bob and Isabel created an amazing company, and I think everyone here is just happy to carry it on.

Parlee is a high-performance bicycle manufacturer headquartered in Beverly, Massachusetts.

Written by Chessin Gertler with the Parlee team | Photography by Chessin Gertler