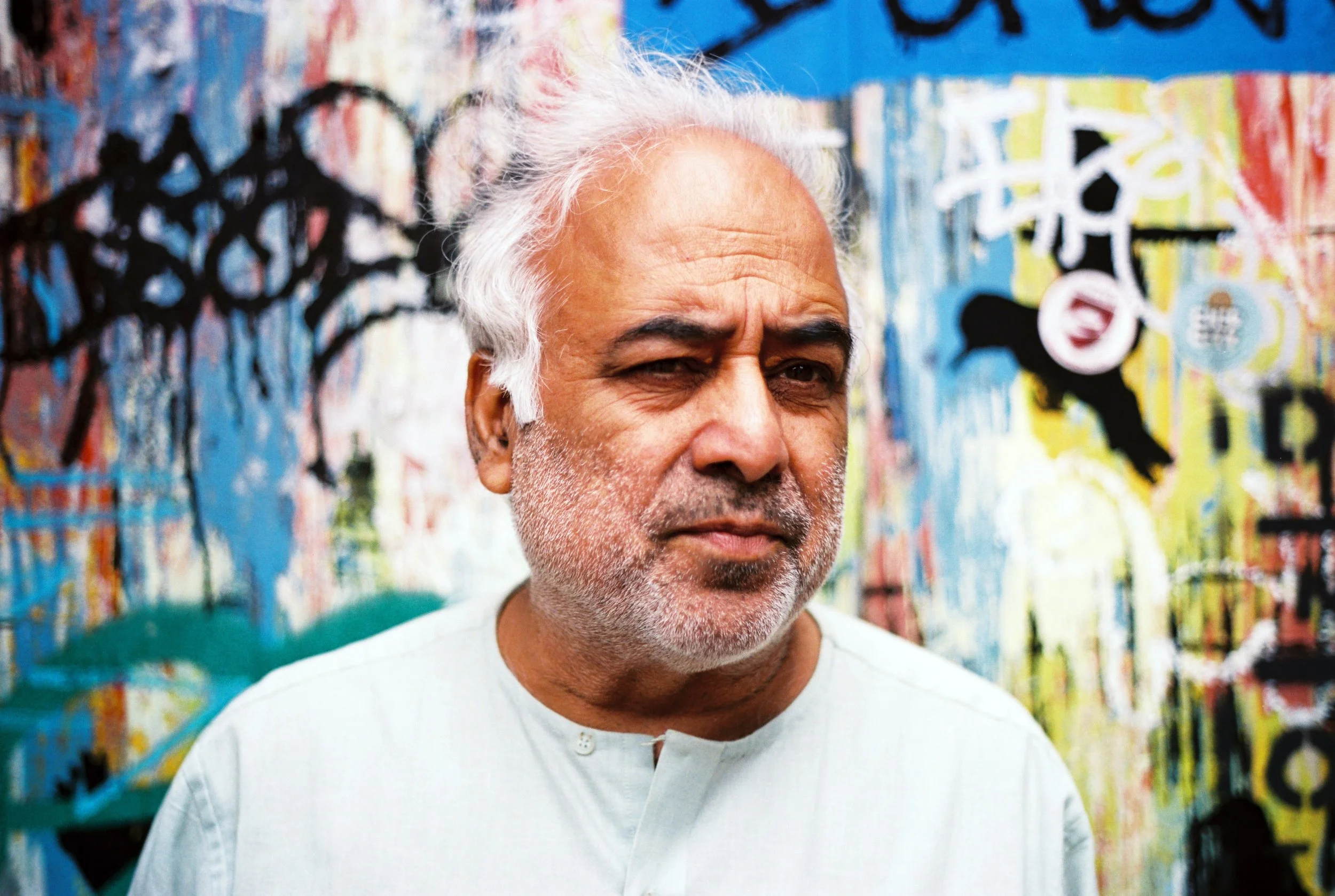

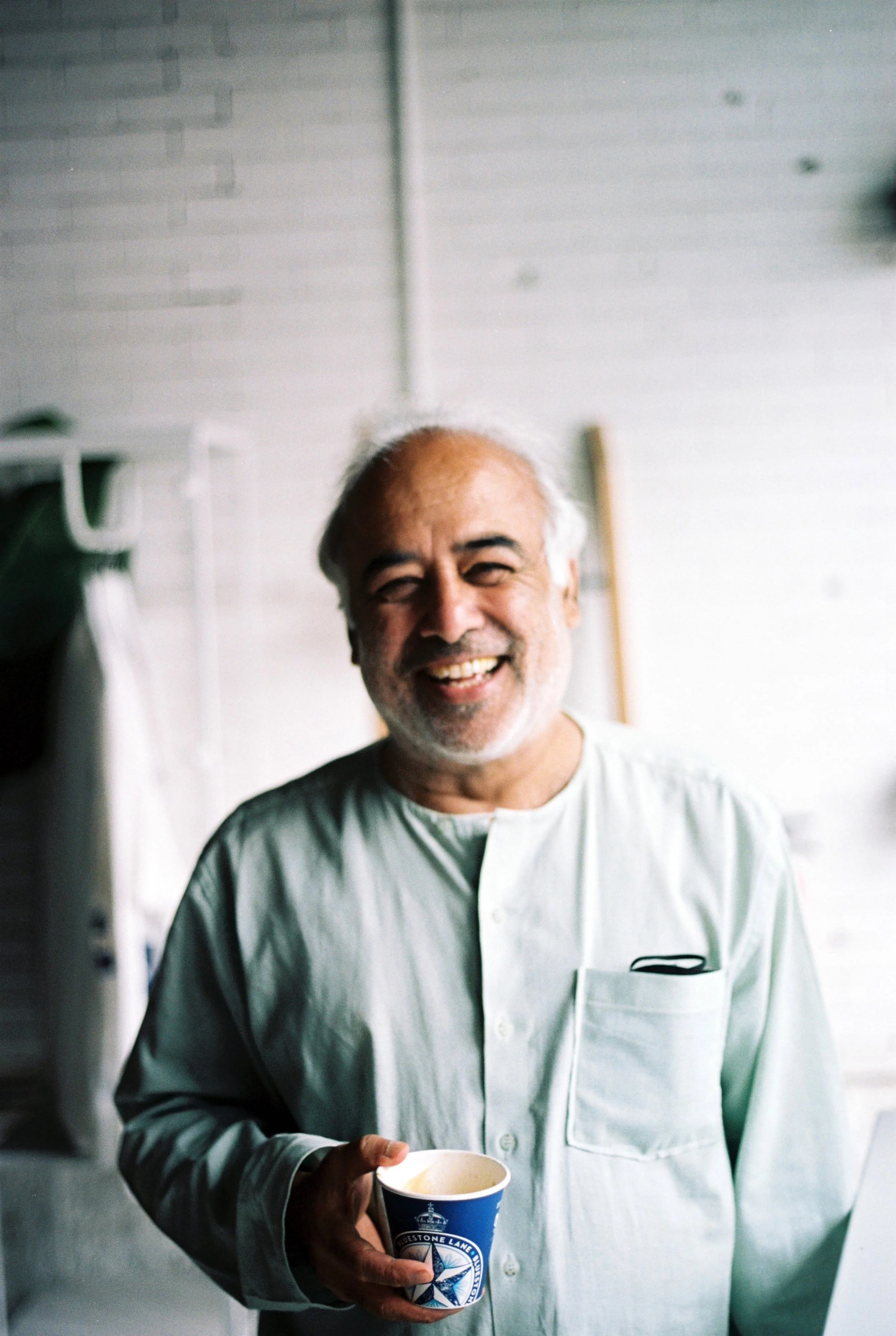

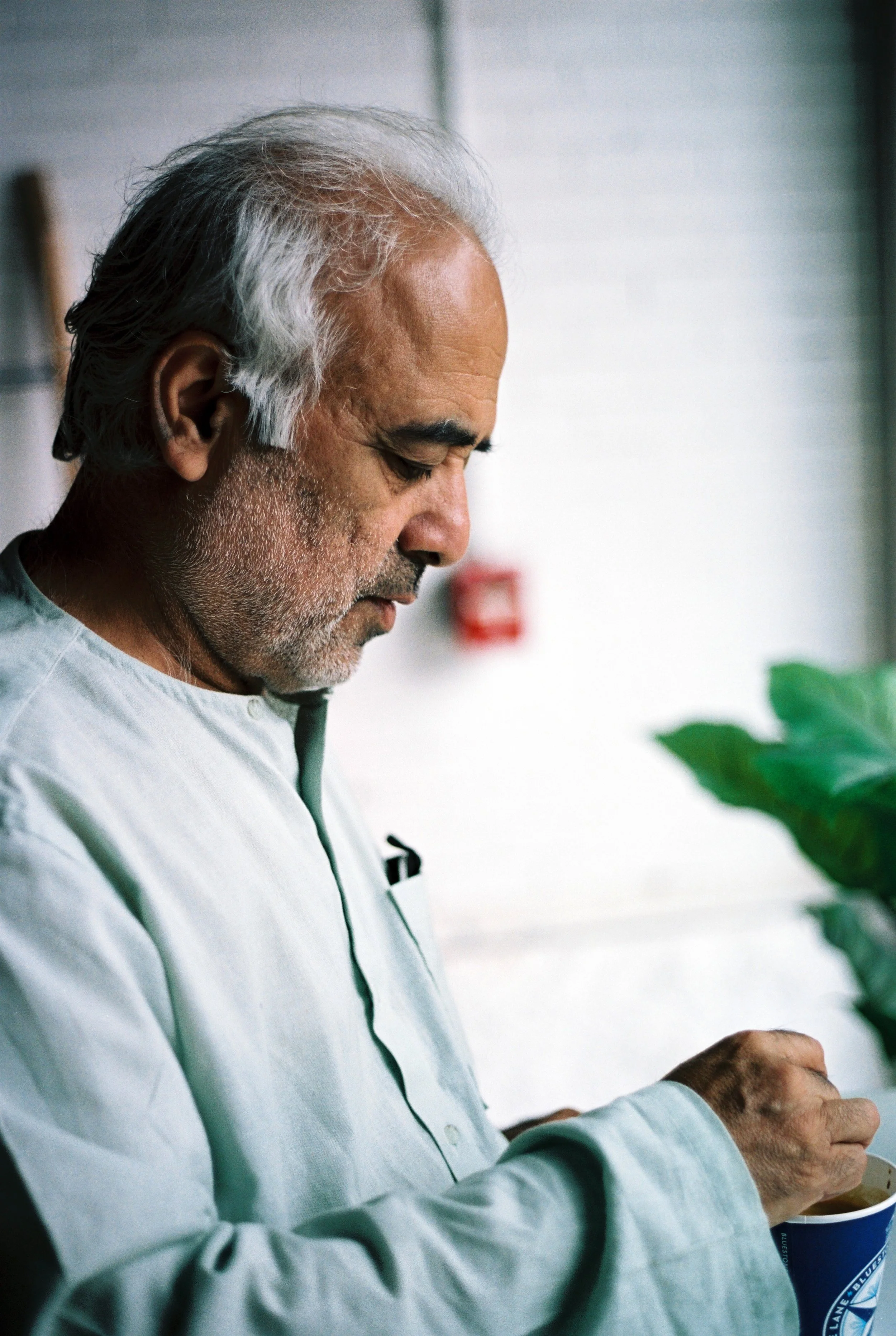

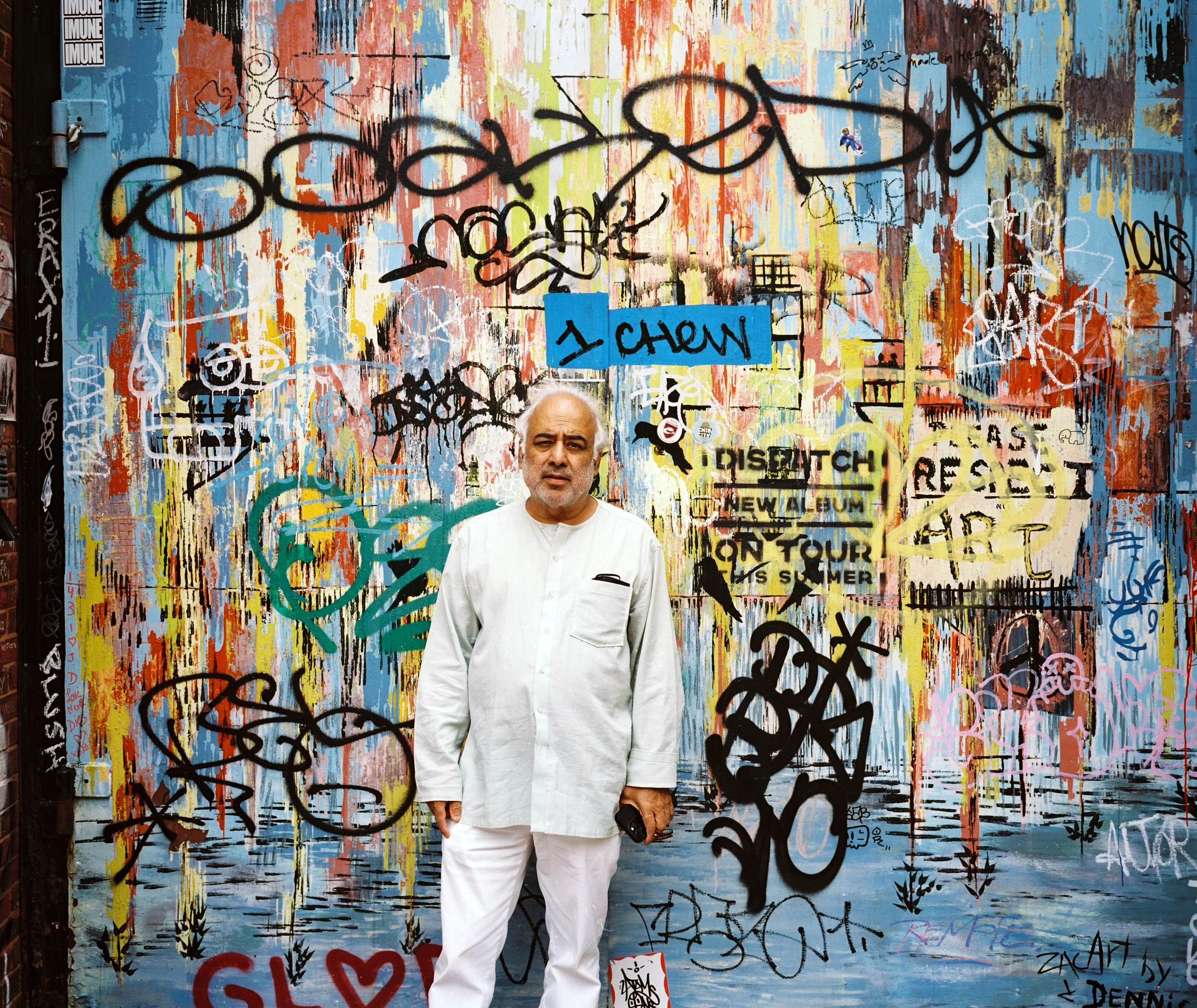

Olympic | Mohammed Ayaz

I grew up with Mohammed Ayaz — my coach, mentor, and friend from the age of nine through high school, into college, and after. With squash’s debut Olympic inclusion set for LA ’28, we sat down to talk about our love for the game — to reminisce, and to reflect on what the sport means to us.

Chessin Gertler: Squash finally got included in the Olympics. For so many players, myself included, that’s huge. We used to talk about it all the time — the frustration that it wasn’t an Olympic sport given its demands. Did you care about that?

Mohammed Ayaz: On one hand, yes — I’m very happy. The Olympics are special. I always loved watching them, all the different sports, the way they’re broadcast. They’re beautiful. Even events you wouldn’t normally follow — you see the athletes break down, cry. It doesn’t matter if they win or lose. They’ve worked for four, five years for that one moment. I could always appreciate that. If they miss it, it’s another four years, maybe never again. And especially in the sports where everything is decided in a hundredth of a second. One wrong stroke, one wrong step — it’s over.

Squash is different — you can be down ten–love and still win. But squash players are very honest athletes. I would have loved to see Ali Farag play in the Olympics. It will be amazing to see Assal, Shorbagy, even Timmy and another American kid or two, on that stage. When I think about what it means to them, I think it’s beautiful. I’m sure when the moment comes, I’ll enjoy it very much.

Chessin: You mean honest in the sense that it’s such a hard sport, the money is limited, and many players dedicate their lives to it purely out of love?

Mo: Exactly. And there are other sports in the Olympics where, if you put things in perspective, squash is a far bigger challenge. It’s not easy to get good at squash. So yes, I think it’s great for the sport, and especially for the players who are still competing.

Chessin: We’ve known each other since I was nine — I’m almost forty now. I remember my first memory of you: walking into the Longfellow Club in Wayland with my brother, and you were coaching. Your daughter, Natasha was there, maybe three years old. Can you take us back — what brought you to Boston, and what was your background before that?

Mo: I didn’t come here for squash. As you know, I grew up in Lahore. Squash was around, but it wasn’t big. There were only a few clubs, a small community. Pakistan’s reputation came from a handful of players — Jahangir, Jansher, ten or fifteen others. If you take them out, there’s not much left. People think squash was everywhere in Pakistan, but it wasn’t.

I was actually on the pre-med track. Over there, high school ends at tenth grade, then you go to college. I was studying biology, chemistry, physics. Squash came later — I was eighteen or nineteen. One of my cricket friends played. I’d go watch him for months.

One day an old marker at the club — he must have been seventy, eighty years old — said, “Why are you here every day? Take this racquet and play.” That’s how it started.

Because of political unrest, classes were interrupted constantly during my first year of college. I suddenly had lots of free time. So I just played and played. That’s when I got good.

Later I went to London. Some of the guys back home told me they had pro contracts, played leagues, and I’d been beating them. So I thought, maybe I can go pro. In London, in the pro league, I didn’t win a match for months. Total reality check. But I ended up playing league at a high level and enjoyed it.

I spent time in New York, some in Europe. New York I couldn’t afford on my own, Europe was always there. Boston was easier.

At Longfellow in the early 90’s, the owner told me, “We’ve gone through five pros in two years. The salary’s twelve or fifteen thousand with health benefits. If you want it, it’s yours.” I said, “Fine — but don’t tell me what to do. Leave me alone, let me run the program.”

Within two, three months I was giving forty, fifty lessons a week. Just showing people how to play properly. Kids especially lifted the program.

Chessin: When you moved to Harvard, you coached a small group of young players in addition to your responsibilities with the teams. What was different about the way you coached? You weren’t just doing lessons; you built this whole little ecosystem.

Mo: At Longfellow I had sixty, seventy kids. When Harvard offered me a position, I knew I couldn’t teach them all. So I called some parents and said, “I can only teach six to eight kids. I don’t want to do lessons. I want a yearly program, built around the school calendar. I need kids who commit, who love squash.”

I told them, three days a week I’ll be teaching, two days I’ll manage practices. Nobody needs five lessons a week, but if they’re playing that much, I’ll make sure they train correctly.

That’s how it started — a small, committed group. Some parents paid, some couldn’t, but once I had enough support, I didn’t care. I wanted kids who loved the game.

And I didn’t train them like mini-pros. Other coaches saw a kid get good and immediately pushed like they were on tour. That misses all the middle steps. I wanted you to learn shapes, dimensions, space, time, tempo, rhythm. How to connect things. How to apply pressure. How to play emotionally. Winning came naturally out of that.

Chessin: I remember when I got to Harvard, the team experience was a little bit of a shock. With you it had been more free-form, creative. Harvard practices and the overall experience were structured and win-driven in a way that I wasn’t totally used to.

Mo: That’s right. With you kids privately, we talked about love, meditation, being free and effortless on court. I knew if you stayed in that space, your competition had no chance.

At Harvard when you got there in 2004, the culture was different. It was about results. Trinity was the big rival. People wanted to win at any cost. That’s okay, but it wasn’t how I saw the game. I still tried to bring the same principles in, but some players took to them, some didn’t.

Chessin: And of course, Satinder Bajwa was central to all of that.

Mo: Yes, Baj. We’d known each other from London—had our ups and downs—but here we became close. He invited me to join him, gave me the space to coach in my own way, and I respected him for that. He cared deeply about the players and the program, and I learned a lot from him.

Chessin: Playing Trinity during those years was one of the most formative experiences of my life. I lost my match to Simba Muhwati. He completely outclassed me. We lost 5–4, but it left a huge mark. The seriousness, the pride, the way Paul Asiante built that team and having an opportunity to compete against them — it was unlike anything else I’d experienced in sport or life. Honestly, I remember that loss in a positive light, not as a negative, because I got to see what greatness really is in a way.

Mo: Yes. We came close. Twice we almost toppled them. Without a trophy, I still feel satisfied. Because I know what we built, and I know what those matches meant.

Chessin: What do you think we loved so much about this sport? When we found it, most of us were already deep into other sports. I played soccer, raced bikes, dabbled as a lacrosse goalie. Some of the kids in our group could’ve gone D1 in baseball or basketball — but we ended up choosing squash.

Mo: You were all good athletes, so first of all, you could play. But also, squash carried a complexity of ideas in many ways different from other sports. Space, time, tempo, rhythm — that’s not just squash, that’s life. The racquet becomes an extension of the hand, the way the body moves with the feet is like dance.

With some of you, I even brought in sound and meditation. Later, when I learned music, I realized that’s what I had been teaching all along — rhythm, composition.

And you all let me be honest. I never had to pretend. That protected me. That’s why many of you went on to unusual paths. It makes me proud. Not because I influenced it, but because what we shared was honest.

Chessin: And part of it too — most of us came from privilege. Our parents wanted us to succeed. There was definitely varying levels of pressure within our group — some productive, some not — but we all had support. That’s not the case for a lot of kids.

Mo: That’s right. You had varying degrees of support — financial, emotional, structural. That isn’t always the case.

Chessin: What has squash given you?

Mo: Everything. Without it, maybe I’d be lost. I’m not the type to exercise just because it’s on the calendar. Squash became meditation. On court the world disappears. I can think about how I spoke to my kids, my wife, reflect on my day.

It gave me my family, my friends. It made me a better person. Without squash, I don’t know where I’d be.

Chessin: And now you’re at SquashBusters — the Boston nonprofit that’s been around for decades, combining squash and academics to support young people.

Mo: Yes. Feels like beginning all over again. The players are at the very start. They don’t have the support you and your group had. So I have to dig deeper.

The staff there is inspiring, very committed. My job is to be there, to share what I know, to help the kids see their opportunity. It won’t be easy, but we’ll get there. I believe that.

Mohammed Ayaz is the Squash Professional at SquashBusters Boston. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts with his wife, Julie. In his spare time, he enjoys playing the saxophone, listening to jazz, and spending time with his three children.

Conversation transcribed and condensed by Chessin Gertler | Photography by Chessin Gertler