Fracture | Kiran Agarwal-Harding

Please introduce yourself

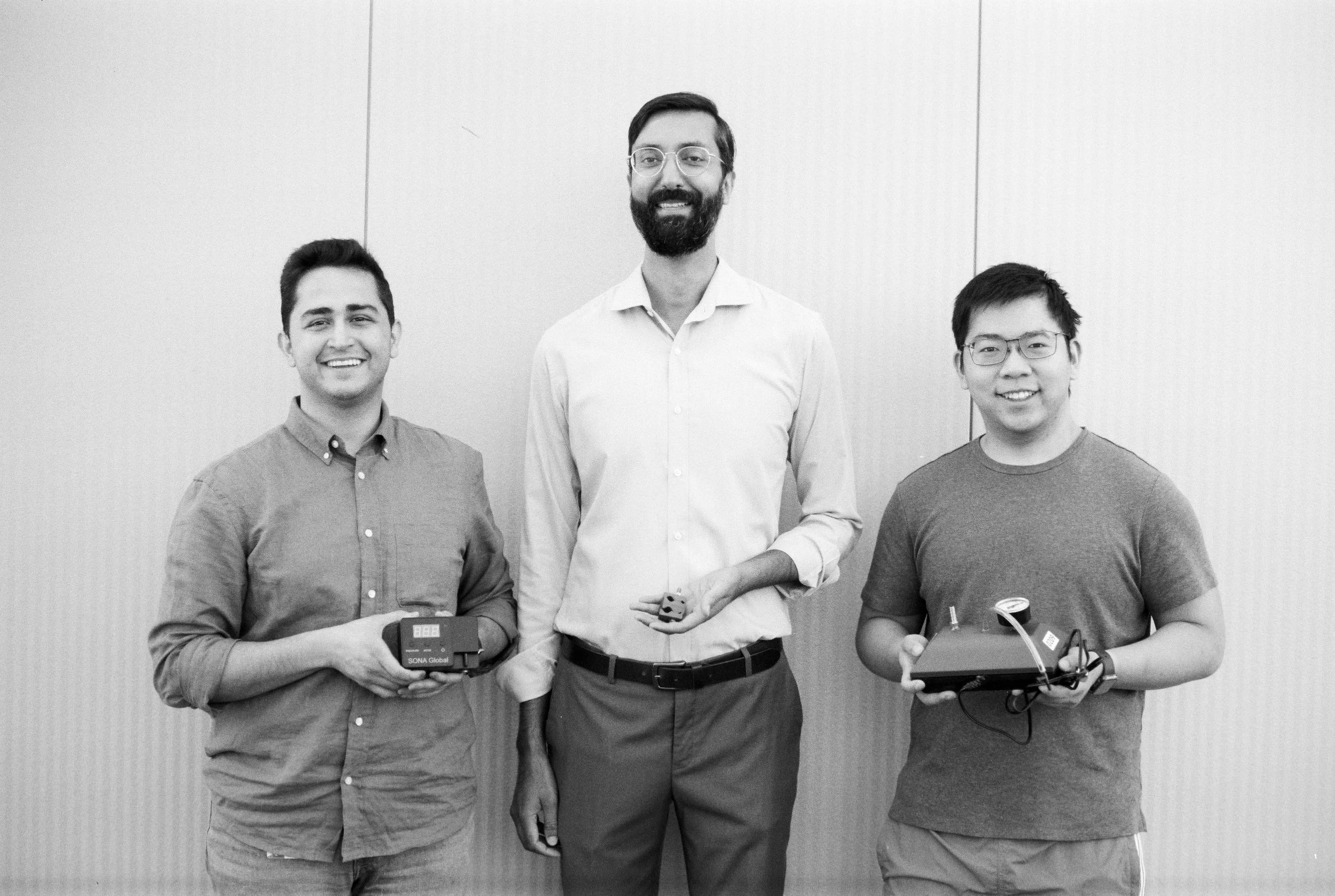

I’m Dr. Kiran Agarwal-Harding, an orthopedic trauma surgeon at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and an assistant professor of orthopedic surgery at Harvard Medical School. I direct the Harvard Global Orthopedics Collaborative and founded SONA Global, a Boston-based nonprofit focused on improving trauma care worldwide through affordable device innovation and multilingual virtual education.

Define orthopedics and the range of what you do.

Orthopedics is surgical care for the musculoskeletal system. The specialty spans trauma, hand, foot and ankle, arthroplasty, pediatrics, oncology, spine, and sports. We use implants—plates, screws, rods, anchors, grafts—to restore function. Nearly everyone in the U.S. will see an orthopedic surgeon at some point in their life. I came to orthopedics through biomedical and mechanical engineering; the field’s mechanical nature matched that background.

How did you choose this path?

I grew up in Ghana and India; my parents worked in education development. As a teenager, my mother had a hemorrhagic stroke while on a work trip. Weeks in ICUs in India and then at Johns Hopkins exposed me to medicine.

I began college interested in oceanography, then shifted to biomechanical engineering at Stanford, volunteered in hospitals as a Spanish translator, and realized medicine was the right fit. The first orthopedic surgery I scrubbed into was a hand case in Tanzania—the anatomy and precision drew me in. Later, in Haiti in 2012, two years after the earthquake, I saw enormous unmet trauma needs. Orthopedics combined engineering, surgery, public health, and global work in a way that made sense to me.

Contrast access in the U.S. with what you see abroad.

In the U.S., there’s about one orthopedic surgeon per 11,000 people. In Malawi, it’s roughly one per 1.3 million—about a dozen surgeons for 20 million people. Musculoskeletal conditions are a leading cause of disability worldwide, and the device cost barrier is significant.

Malawi itself is a small country in southeastern Africa, about the size of Pennsylvania, with one-third of its area covered by Lake Malawi. It is landlocked, bordered by Mozambique, Zambia, and Tanzania, and has very few natural resources. More than 80 percent of the population lives in rural areas, with about 70 to 80 percent relying on subsistence farming. Food insecurity is widespread—about 60 percent of Malawians face some form of it, meaning they wake up not knowing where their next meal will come from. Around half the population lives below the national poverty line of less than two dollars a day.

When I first began traveling there in 2016, Malawi had the fourth-highest road traffic mortality rate globally. Now it ranks ninth, not because things improved but because other countries got worse. Globally, trauma causes around five million deaths annually—more than HIV, TB, and malaria combined. And that figure doesn’t include the far larger number of people living with lifelong disability after injury.

What kinds of injuries do you treat most often, and how do they compare across contexts?

Upper-extremity trauma—wrist fractures, elbow dislocations—can be profoundly disabling. Without surgery, patients may suffer chronic pain, instability, and loss of motion. In Boston, these injuries are treated operatively to restore anatomy and function. In rural Malawi, the same injury might only be splinted, often with improvised materials like cardboard or towels. There’s evidence linking upper-extremity trauma to long-term depression, PTSD, and persistent pain.

Children are especially vulnerable. During mango season in Malawi, many fall from trees and fracture their elbows. In the U.S., those cases receive urgent surgery. In Malawi, the standard is “straight-arm traction”: tape on the forearm, a rope to the ceiling, the arm elevated for days, then blind manipulation and splinting. Four years later, about 70 percent of those children still had pain, functional limitations, or deformity affecting school and daily life.

Lower-extremity injuries carry their own burden. A pilon fracture—high-energy ankle trauma from a fall or crash—often leaves long-term health outcomes worse than chronic conditions like congestive heart failure or renal disease. These injuries can determine whether someone can walk, work, or avoid life-threatening complications.

In Boston, a femoral shaft fracture means surgery within 24 hours. We stabilize it with an intramedullary nail, and the patient can often walk the next day. In Malawi, the same injury is treated with skeletal traction. A reused, dull pin is hammered through the shin—sometimes without anesthesia—then weights hang off the bed for weeks. Patients lose muscle, knees stiffen, legs shorten. Families lose income for months. It’s painful, socially devastating, and often lethal.

What’s driving the trauma burden in places like Malawi?

Motorcycles are a big factor. Cheap motorcycles have exploded in popularity. For about $500, families can access new livelihoods—transport crops to market, carry passengers, or reach clinics. Politically, this mobility is celebrated, so regulation is minimal.

But unregulated motorcycles are dangerous. Maintenance is poor, brakes and tires fail, helmets are rare, and it’s common to see multiple passengers—including children—on one bike. Roads lack lighting and pedestrian protections. Hospitals are flooded with patients with open fractures. It’s a double-edged sword: the same mobility that expands opportunity also drives injury and poverty.

How did these realities lead to SONA Global?

We started by listening to surgeons in places like Malawi. They knew outcomes were poor but lacked published data to advocate for change. Over the last decade we built evidence and a network, and then focused on two bottlenecks: affordable devices and accessible training.

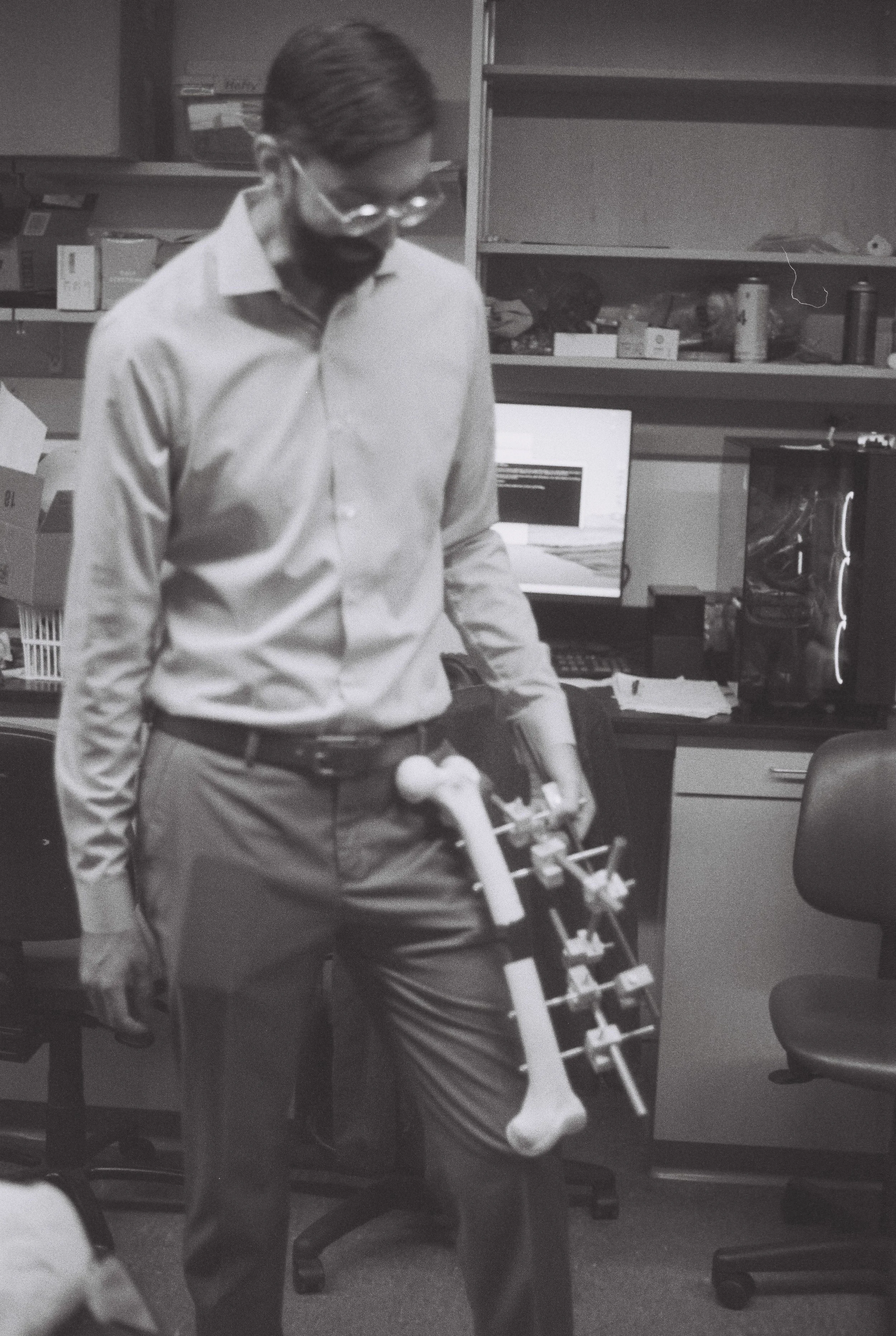

Describe the devices.

AEFIX (Affordable External Fixation) is a low-cost clamp for external fixation—pins into bone connected by rods outside the limb to stabilize fractures, especially open injuries. Standard clamps in the U.S. are about $600 each; a temporary frame can cost $4,000 and is single-use. Our clamp is about 98 percent less expensive, with comparable mechanical performance. We stripped it down to essential requirements—hold the pin and rod securely, be versatile—and designed it from four identical extruded aluminum components that can be manufactured locally. Surgeons in Rwanda tested it on sawbones and liked it, finding it easier to use than some cheaper knockoffs. We now have regulatory approval and a clinical trial in Sri Lanka, with plans to expand in Southeast Asia and Africa.

Standard external fixation clamp (left) and AEFIX (right),

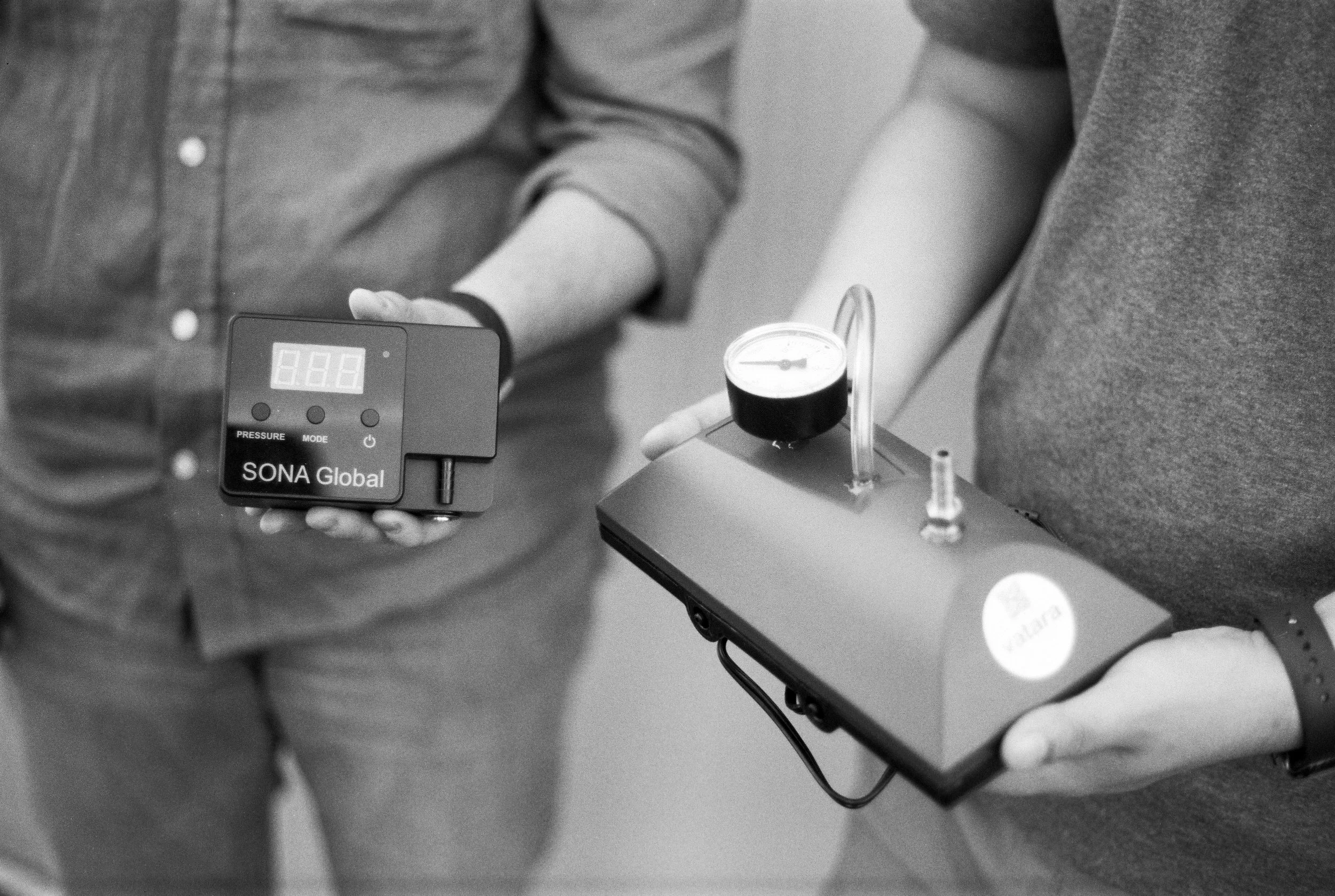

Our second device is VATARA, a negative-pressure wound therapy system. Standard hospital pumps in the U.S. cost over $40,000. Ours is about $500—a similar 98 percent cost reduction. It applies gentle suction to seal wounds, remove contamination, and promote healing. NPWT is standard for open fractures, infected wounds, diabetic ulcers, and pressure sores. Our goal is a safe, standardized, affordable system instead of improvised or prohibitively expensive ones.

Prototype (right) and current version (left) of VATARA, a negative-pressure wound therapy system.

Where is SONA Global headed?

On devices, we’re moving from lab validation to clinical trials to broad regulatory approvals, aiming for a sustainable model. In very low-income countries like Malawi, that means at-cost pricing or donation via humanitarian partners. In middle-income countries and private hospitals, tiered pricing can sustain operations, fund R&D, and support donations.

On education, we’ve built a multilingual program—virtual and in-person. We’ve reached 4,500 surgeons and trainees in 125 countries. About 2,000 surgeons connect daily, sharing cases and advice. We’ve created hundreds of resources. And we emphasize mentorship and follow-up because many injuries require multiple procedures and long-term care.

Disparities also exist inside the U.S. Our group is studying access among incarcerated patients; delays are common, including for wrist injuries. We’ve published on access for American Indian and Alaska Native communities. In Navajo Nation, for example, fractures are often managed non-operatively by primary care doctors, with long, expensive transfers if surgery is needed. Focusing on the poorest patients—whether in Malawi or the U.S.—lifts the standard of care for everyone.

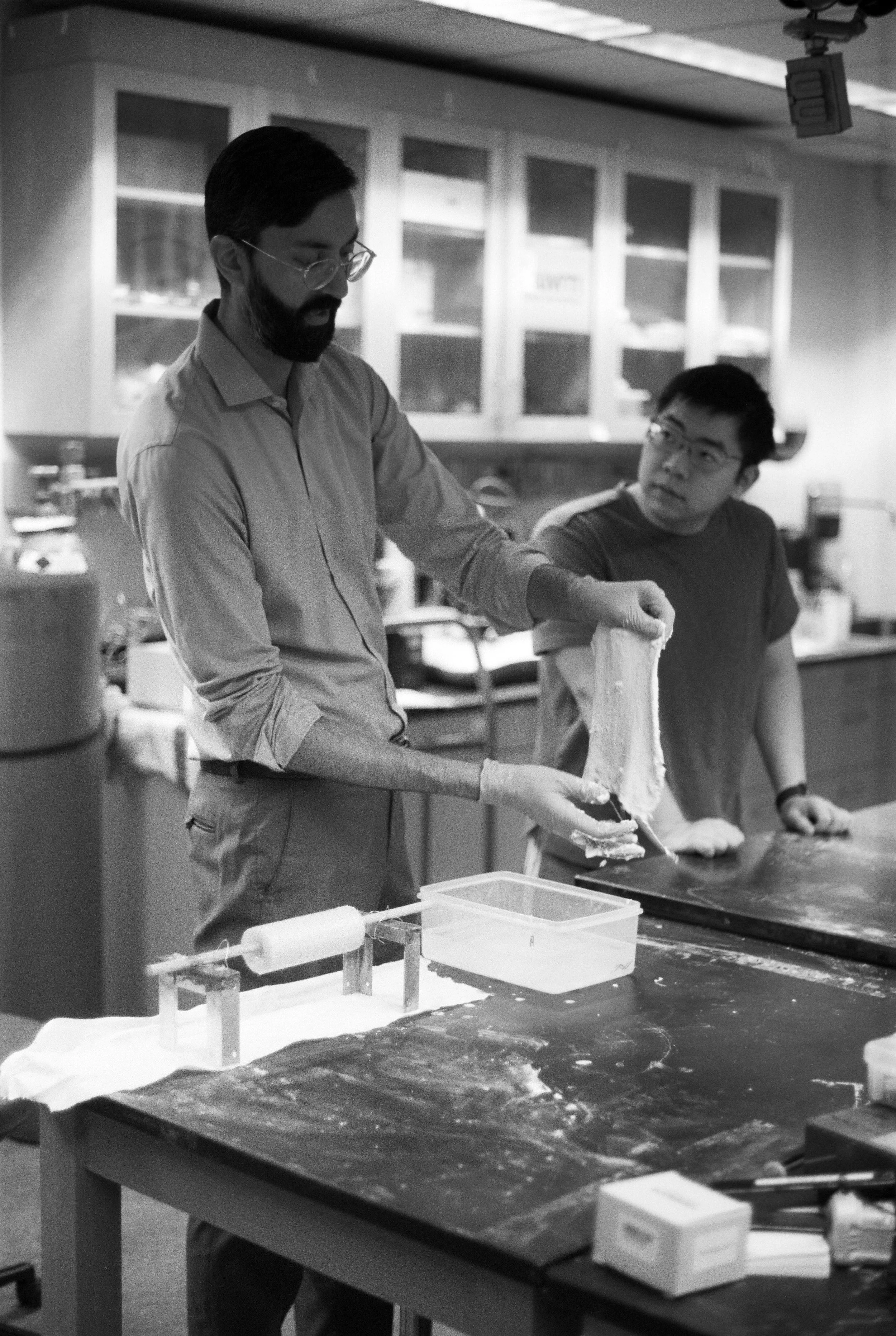

Harvard medical student Jerry Zhang and postdoctoral fellow Alireza Mirahamdi working with a simulated wound model and VATARA

What is the end state you’re working toward?

Essential trauma care that is universally available, regardless of birthplace or income. Concretely: local manufacturing hubs in Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia embedded in academic ecosystems; a tiered pricing model that sustains operations and subsidizes the poorest; and global education so every graduating resident can perform safe, effective core trauma care—external fixation, negative-pressure wound therapy, fracture reduction, splinting—with ongoing mentorship and standardized evaluation.

Our novelty is radical affordability, and the systems that keep it affordable: design, manufacturing, logistics, pricing, and a quality-focused, data-driven education network. That’s how we get to a world where nobody lives in lifelong pain or disability because they were born in the wrong place.

Kiran J. Agarwal-Harding, MD, MPH is an orthopaedic trauma surgeon at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Assistant Professor at Harvard Medical School. He founded the Harvard Global Orthopaedics Collaborative and SONA Global, a nonprofit that develops affordable surgical innovations and provides free education to improve trauma care in underserved regions. In Boston, he cares for patients at a Level 1 trauma center, trains the next generation of surgeons, and leads research and innovation projects. Internationally, he partners with colleagues in Malawi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, and Sri Lanka to expand training, mentorship, and advocacy. Raised in Ghana, India, and the United States, he brings a global perspective shaped by his education at Stanford, Harvard, and Columbia.

Conversation transcribed and condensed by Chessin Gertler | Photography by Chessin Gertler