Coast | Scott Muhlstein

Being a first-year teacher is hard—often the hardest year of a teacher’s professional life. In early 2018, I was living this reality, struggling day in and day out in my high school history classroom in the Boston Public Schools. Graduate school doesn’t prepare you for what to do when you call out a student for disrupting learning for twenty-five students, and the student responds by saying, “Actually, I’m disrupting learning for twenty-SIX students!” Or for what to do when you stay up all night planning lessons but forget to for your Period 6 class—and they’re about to come screaming through the door. Or how to intervene when you’re in a parent-teacher conference and the parent pulls out his phone to argue with you about the gradebook but instead accidentally shows you a screen with pornography playing, sound and all.

It was early springtime, and my colleagues, friends, and family were all asking what I would be doing with my coveted summer break.

“Are you going to teach summer school?”

“Are you going to bartend? My friend who is a teacher bartends during the summer and actually makes good money!”

“Have you thought about traveling through Europe?”

None of these, and many other options, seemed appealing to me at that moment, but I did know that I wanted to do something with my time off. That’s why you become a teacher in the first place, right?

All kidding aside, my convictions about the importance of public education and equity were still burning strong, but I definitely did need the summer to get away from it all and ponder how I could become more effective in my role and actually make the difference that I wished to make within a difficult system.

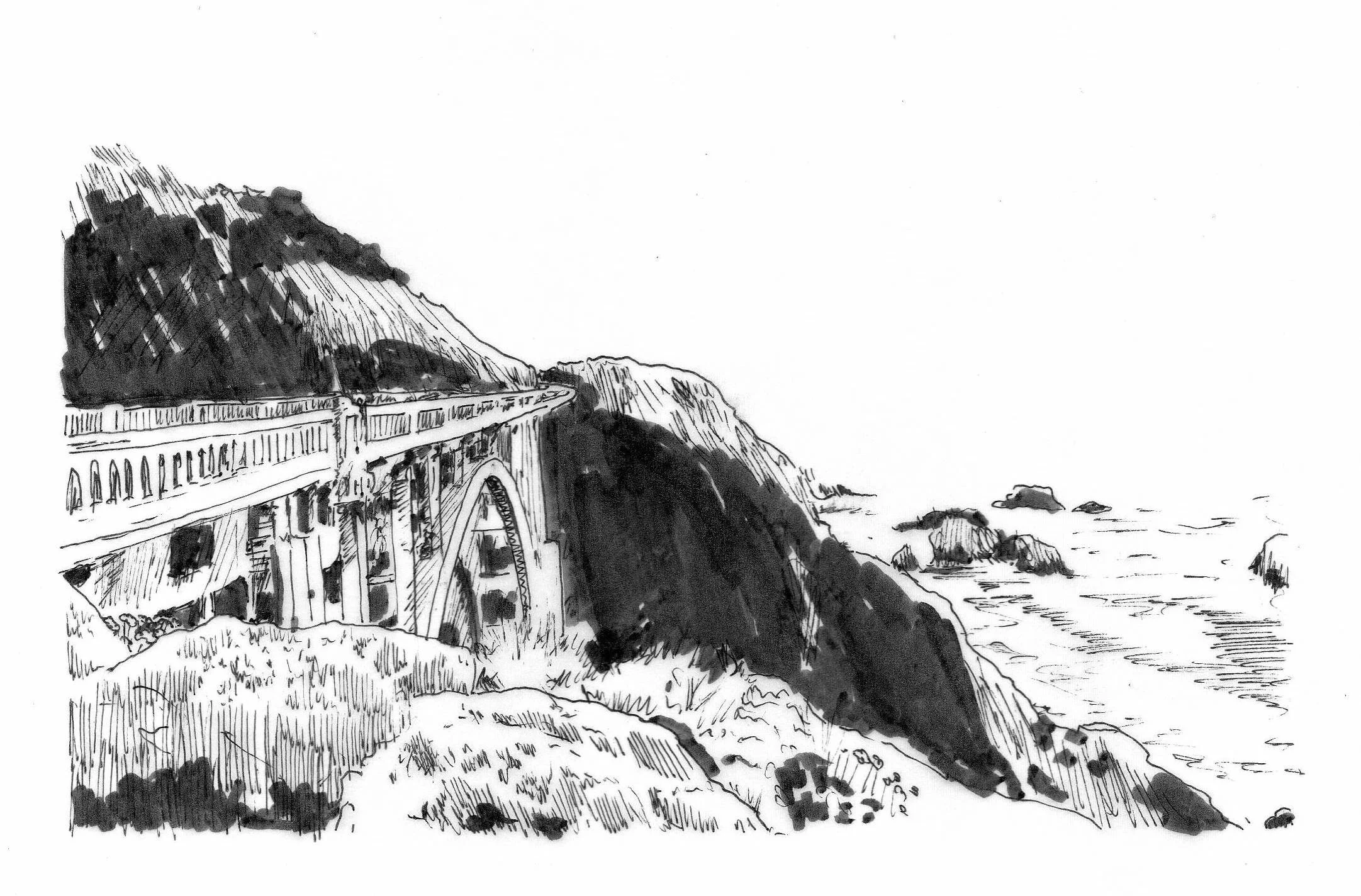

Fresh off of reading Dervla Murphy’s Full Tilt, a true story about an Irish woman who rode her bike from Ireland to India in the early 1960’s, I thought that a great way to do this type of thinking would be on a bike saddle. The Pacific Coast always intrigued me, and my brother was living in Santa Monica at the time, so I figured I could ride there from Portland (where there was a flight that fit my first-year teacher budget).

Now, some people are born to be cyclists, and you undoubtedly have seen these people (or are one yourself). The spandex seems fused to their skin, their bikes make that loud whirring sound from their freewheel while cruising downhill, and their helmets are straight out of Coneheads—but rotated 90 degrees. I am not one of these people. But I figured that my experience riding around the neighborhood growing up and surviving my commute down Boston’s Dorchester Avenue corridor would be enough to get me through my Pacific Coast journey.

Fast forward a few months, and I’m on the plane to Portland with a plan to rent a bike at a local shop there for my voyage. When I got there, the employee at the shop asked me what my trip itinerary looked like, given that I was renting the bike for about a month. I told him my plan, and he gave me a skeptical look. He looked me up and down and could tell I wasn’t a hardcore cyclist. Maybe it was my thin polyester running shorts or my oversized cotton T-shirt that gave it away, or the helmet I was carrying that looked like it was from my childhood.

He asked me what type of handlebars I wanted installed on the bike—flat bars, drop bars, or butterfly bars?

“Uhhh, what do you recommend?” I said, not knowing the distinguishing characteristics or benefits of each style.

Did I want flat pedals or clipless?

“Clipless,” I said, thinking that meant pedals that didn’t have a clip and therefore would work well with my floppy, two-year-old Asics sneakers. (I only recently learned that clipless pedals are named that way because older versions had true toe clips and external toe straps.)Then he asked if I had a pair of cycling shorts, to which I replied that I would be riding in what I was wearing and had an extra pair of shorts in my saddlebag. He had me sold after explaining in excruciating detail how much of a “pain in the buttocks” the tour was going to be without them.

I left the bike shop with a lighter wallet and new nervousness. Did I know enough about cycling and the gear associated with the sport to be able to complete this ride? Was I a complete fool for planning an itinerary that required riding approximately 50 miles per day? Would I go back to Boston and have to tell my friends and family that I wasn’t able to complete the journey?

These questions swirled in my head as I mounted the saddle and started to ride toward the Oregon coastline.

The first day was beautiful—pedaling through lush forests with uphills that were challenging but not overwhelming, and downhills that felt exhilarating for someone used to riding mostly through urban Boston. I made it to my campsite, set up, cooked a hearty dinner, and retired early to my tent. A successful Day One in the books!

I woke up the next morning almost paralyzed from the waist down. My legs were so stiff I had to use my arms to claw myself out of my sleeping bag. Breaking down my tent took nearly an hour—each bend forward felt like an immense chore. I felt like Bill Bryson’s friend and hiking companion, Stephen Katz, in A Walk in the Woods, who was so out of shape and frustrated that, after just one day on the Appalachian Trail, he began hurling his gear off the side of a cliff. The whole time, I kept thinking, How am I possibly going to ride today? If there’s even a slight uphill, I’ll probably just roll backward and end up camping here again.

I did survive the hills that day, and as the time and miles rolled on, my legs and attitude became stronger and stronger. Gliding down Oregon’s coastal capes with sweeping ocean vistas and the cool marine layer enveloping me was like nothing I had ever experienced. It was the type of joy that only a dose of nature—and powering yourself through it—could bring. I made friends with other cyclists who were also making their way down the coast, something that I did not anticipate happening. We rode long miles, mostly spread out, mostly silent, but in the evenings we’d set up camp along the quiet beaches and cook up concoctions of rice, beans, tomato sauce, packaged vegetables, and whatever else we happened to be carrying at the time. There was singing, stargazing, and the sound of waves—the stuff of Pacific Coast dreams.

One day, after splitting up with my group of riding buddies, I was taking a breather along the road outside of Crescent City when a beat-up red pickup truck pulled over next to me. The man inside asked where I was riding to that day, and when I told him my destination, he asked if I’d like to camp in his yard. My tired body and mind weren’t thinking like a Bostonian—skeptical about what this man’s intentions could be—so I said sure, and took down his address. When I arrived at his home, I was invited in for a meal of frybread and beans, and then proceeded to spend hours on the couch with him watching Family Guy and The Simpsons, with copious amounts of ice cream and snacks. I was struck by the kindness of strangers and the feeling that people look out for you when you’re on an adventure, making sure that you have what you need to carry on.

For most of the ride, my mind stayed relatively present and in touch with the gorgeous surroundings of Oregon and California’s coastline. There were times, also, when I started to feel a creeping selfishness about being able to spend a summer riding my bike out in nature, knowing that the students I worked with did not have that luxury. For many of them, the summer was a time spent at home playing video games, maybe at a local YMCA, or at a summer job. Extended time out in nature was not usually an option that was accessible. The outdoor opportunity gap was not something I could “solve”, but I pledged to use my privilege and resources to make some sort of inroad upon returning to Boston. My students deserved to experience the feelings of trying something new, being out in nature, challenging oneself, making friends, and maybe even receiving support or nourishment from an unexpected place.

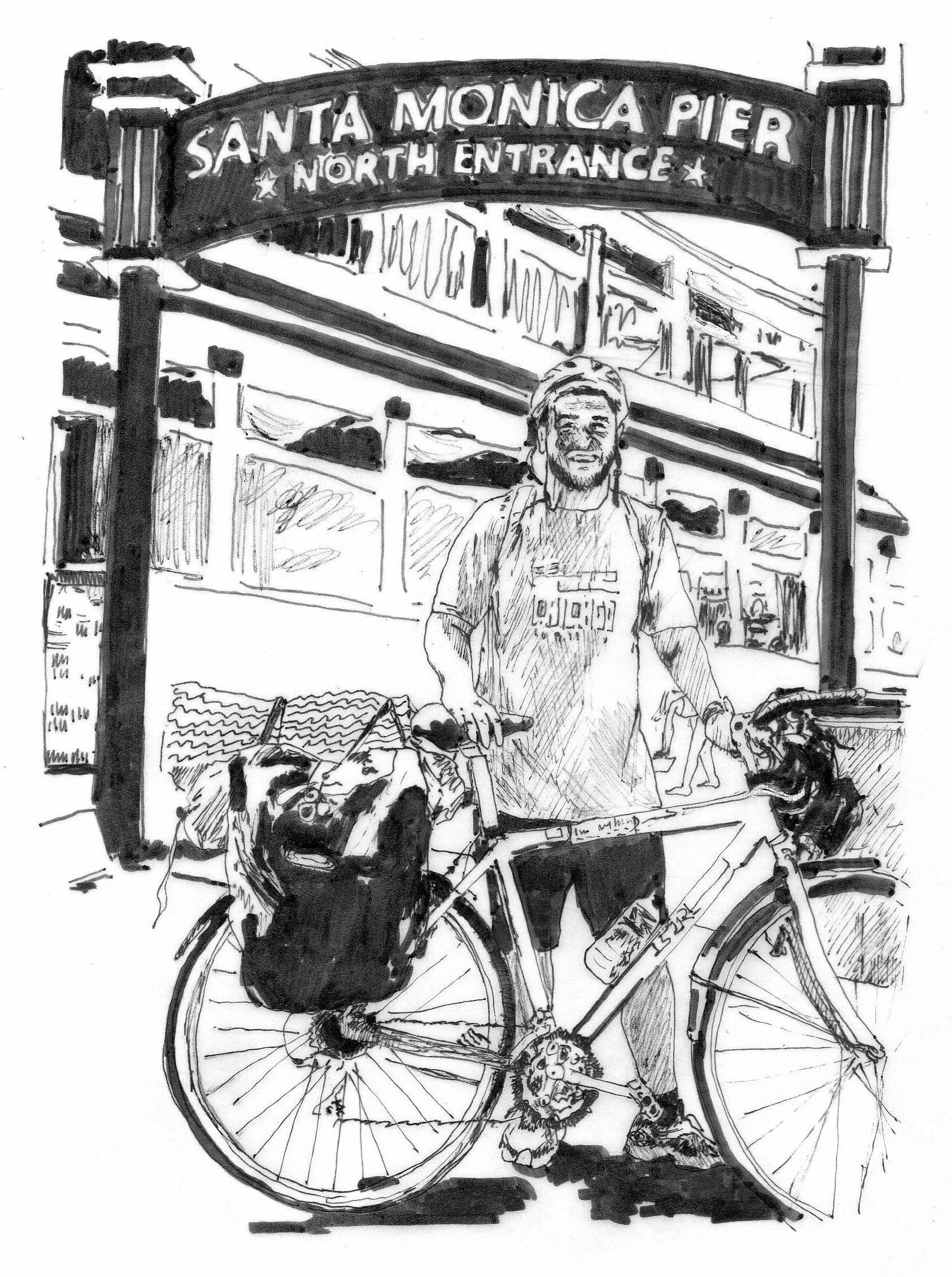

At the end of the month, I arrived at the Santa Monica Pier—tired and sweaty, but full of joy and new inspiration for the work ahead.

There were so many special moments that summer, and none of them would have been possible if I had stayed in my comfort zone or let my imposter syndrome take over while in that bike shop in Portland. Upon returning to teaching, and with a very supportive and passionate group of administrators and community members, I was able to start the first Outdoors Club at the school, taking students on cycling, hiking, canoeing, kayaking, and skiing trips throughout New England. The young people who had the courage to join in on these opportunities were able to try new activities, make new friends, struggle through challenges, and hopefully take all of these new experiences back with them into their communities and apply the lessons they learned in their everyday lives. For some, this even led to a desire to explore careers in the outdoor industry or mentor others who were getting involved in similar programs around the city. It was a relatively small change in the grand scheme of things, but one that I was proud to help spur on.

Since that eye-opening cycle tour in 2018, I’ve left Boston and now live in the red rock foothills of the Chuska Mountains on Navajo Nation. I’m still teaching, still cycling, and still trying to find ways to combine the two. There are a number of inspirational people and organizations here leading outdoor excursions, including mountain biking and cycling trips, for young people on Navajo Nation. It is our hope to inspire others to get outside and have an adventure—even if they don’t always feel equipped to do so. After thousands of miles of cycle touring in numerous states and countries, I’ve found that a good pair of cycling shorts can only do so much to alleviate pains in the buttocks, but they are a welcome addition.

Scott Muhlstein is originally from New Jersey and has spent the better part of the past decade as a public school educator. He is currently pursuing graduate studies in educational leadership and lives in northern Arizona with his wife and their Rez dog, Nova.

Written by Scott Muhlstein | Illustrations by Piece Whang